July 2, 2018 — University of Washington (UW) Medicine cardiologists have developed a tool to predict which heart failure patients stand to gain most, and least, from an implanted defibrillator.

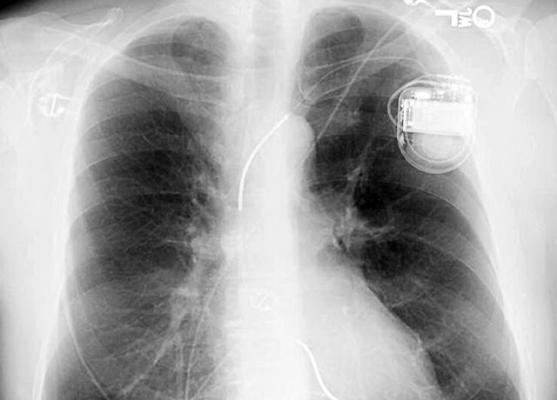

About 30 years ago, doctors started putting implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) in patients who had survived a sudden cardiac arrest. These palm-size devices, wired to the heart, could stave off another such event by recognizing a dangerous rhythm and providing a lifesaving shock, returning the organ to normalcy.

In subsequent years, cardiologists developed a rationale to place ICDs in people who had not sustained a cardiac arrest but who had a diagnosis of chronic heart failure and other risk signs.

But as the population of implant recipients grew, cardiologists learned that many devices were giving shocks when no peril was evident. Many inappropriate jolts landed patients back in the hospital – and each needless shock stoked fears of another. What’s more, studies began to show that two-thirds of ICDs, mostly in older people, never gave even one shock; those patients died of unrelated causes, challenging the thinking behind their implants.

“This is the main reason that ICD placements have diminished in recent years. Doctors want to avoid these downsides, and they feel less able to predict who will benefit,” said Wayne Levy, a professor of medicine (cardiology) at the University of Washington School of Medicine. His research focuses on prognostic risk modeling in heart failure.

Levy and colleagues’ model will help doctors identify not just which patients merit consideration for an ICD, but which are likely to benefit most, and least, from the device. The model’s predictive value is demonstrated, Levy said, in a research paper published in the Journal of the American College of Cardiology-Clinical Electrophysiology.1

“We have validated the model with a gold-standard test: applying it to a previous trial in which patients were randomized to an ICD or no ICD – to see if the model would accurately predict, among those who got the device, who would benefit most. And the model worked very well,” he said.2

It is the very same Seattle Proportional Risk Model that Levy and colleagues published in 2015 to establish which heart failure patients were at greatest risk of sudden death.3 The only difference is presentation: Now the model is the brains to an online tool that any cardiologist can use, Levy said, to enter patient-specific data to discern the likelihood of an individual’s prospective ICD benefit.

The need for such a tool has existed for years but was heightened in February when the Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services (CMS) announced it would cover future ICDs only if physicians could document a “shared decision-making” process had occurred with patient candidates.

That mandate, though, is inadequate because “the suggested model for that conversation simply identifies the benefits and harms associated with the device,” Levy said. “The illustration of benefit is based on the average patient; it likely doesn't represent the patient sitting in front of you who may be 15 years older with diabetes or lung disease or some other condition.”

As with CMS, hospitals are scrutinizing costs and patient satisfaction like never before. Levy thinks an easily accessible tool whose methodology has been validated gives cardiologists an evidence-based foundation for those conversations with patients.

“To be clear, the model isn’t making a recommendation about whether to place a defibrillator; what we’re doing is saying, if you put one in, this is the potential magnitude of benefit or non-benefit based on this tool. The physician and patient need to make their own conclusion whether to place an ICD,” he said.

For more information: www.electrophysiology.onlinejacc.org

References

3. Shadman R., Poole J.E., Dardas T.F., et al. "A novel method to predict the proportional risk of sudden cardiac death in heart failure: Derivation of the Seattle Proportional Risk Model," Heart Rhythm, Oct. 2015. DOI: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.hrthm.2015.06.039

January 05, 2026

January 05, 2026