Recent months have signaled a new and exciting era in the dynamic world of

structural heart disease (SHD). The

COAPT Trial has demonstrated a significant mortality benefit in medically-optimized heart failure patients with severe functional mitral regurgitation who undergo MitraClip implantation.[1] In March 2019, the low-risk transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) trials of

PARTNER 3 demonstrated superiority with the Sapien valve, while the

CoreValve Evolut established comparable outcomes as compared to surgical aortic valve replacement.[2,3] The striking results of these robust clinical trials were literally received with a standing ovation at the 2019 American College of Cardiology (ACC) Scientific Sessions, as they represent new hope for many patients with debilitating symptoms.

As the field of SHD interventions continues to evolve and grow, societal and industry recognition of the importance of a dedicated heart team approach is critical to optimizing patient care and maximizing procedural safety. A fundamental player in every heart team is the interventional imager.

Structural Heart Imaging Evaluation of the Aortic Valve

Interventional imaging has undoubtedly revolutionized the field of SHD. Interventional Imagers are intimately involved in almost all steps of a structural intervention. They serve as the orchestrators of the heart team. To competently and effectively perform their tasks, they need to be highly-skilled and trained in multi-modality imaging with a special focus on pre-procedural planning, intra-procedural guidance, identification of complications and post-procedural follow-up.[4,5,6] Despite the indispensable function they play, their roles continue to be under recognized by hospital administrators and by insurance payers alike. This article highlights the instrumental role of the interventional imager and the challenges faced by those in this new specialty field of medicine.

Interventional Imagers play a key role in the following stages of a structural intervention:

1. Diagnosis

Interventional imagers are involved in identifying and evaluating patients with SHD. Their knowledge of the limitations of different imaging techniques empowers them to integrate information from multiple imaging modalities to determine a patient’s diagnosis, prognosis and candidacy for an intervention. Additionally, their familiarity with the different transcatheter devices, procedures and surgical options enables them to assist the heart team in patient/procedure selection and optimal procedural timing. In addition, the interventional imager can identify procedural risks and benefits specific to each novel device, shaping the heart team’s management.

2. Decision Making Process

Interventional imagers play a crucial and active role in multi-disciplinary heart team meetings, which determines the best treatment strategy for patients with SHD. In addition to interventional imagers, the heart team includes interventional cardiologists, cardiothoracic surgeons and cardiac anesthesiologists. Such teams are invaluable in tackling the complex decision making process involved in the management of SHD, as each step of the decision making process requires special expertise and skillset.

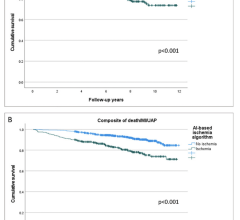

Evaluation of aortic stenosis (AS) is a good case example. The diagnosis is traditionally identified by echocardiography. However, not uncommonly, confirmation of severity is not so clear, particularly in patients with low-gradient aortic stenosis. The assessment of aortic valve calcium scores in patients with low flow, low gradients aortic stenosis can help in the assessment of AS severity and guide management decisions.[7] The pre-procedural planning for transcatheter valve delivery, valve size and access routes are determined by the interventional imager using advanced post-processing analysis of cardiac CT images for TAVR (Figure 1).

CT data must be integrated with echocardiographic findings to provide anatomic and physiologic understanding of the disease process. Annular measurements allow for appropriate device selection while coronary artery height predicts risk of coronary obstruction. Aortic root features such as extent of calcification and steepness of the angulation could favor one valve platform vs. another. As noted in the recent PARTNER 3 trial, approximately 20 percent of screened patients were excluded from TAVR due to cardiac CT defined anatomic exclusions including severe left ventricular outflow obstruction, calcium and an adverse aortic root.[2] This highlights the crucial role of anatomic risk stratification yielded by CT, which requires a higher level of scrutiny in this growing group of low-risk patients.

In patients with mitral valve regurgitation (MR), a thorough serial review of echocardiographic images of the mitral valve is required before a structural intervention is planned. No longer solely a diagnosis of lesion severity, but the etiology/mechanism of MR is key to be determined using 2-D and 3-D TEE imaging. Decisions about replacement vs. repair, either surgically or via transcatheter interventions, will be based on heart team discussions accounting for many factors including anatomical as well as patient’s surgical risk and comorbidities. The success of a transcatheter MitraClip intervention relies heavily on the understanding of pre-procedural echocardiographic findings and the technical skills of the operator. For ongoing transcatheter mitral valve replacement trials, cardiac CT has been instrumental for patient selection by identifying those with potential risk for catastrophic complications such as left ventricular outflow obstruction.[8]

The revolution of transcatheter interventions continues to expand now including the once forgotten (tricuspid) valve. Multiple devices for the treatment of tricuspid regurgitation are currently under clinical trials. Imaging will remain a key aspect in providing patient selection, procedural planning and guidance for such interventions.

3. 3-D Imaging: Printing, Fusion, Pathway to Imaging

With increasing complexity of SHD interventions, not all procedures are performed using traditional surgical methods. Where a decade prior, patients were limited to the options of surgical aortic valve replacement (AVR) or hospice, transcatheter therapies have opened patients’ and the heart teams’ minds to searching for and creating novel approaches for patients without necessitating cardiopulmonary bypass. In the setting of paravalvular leaks around failed surgical devices, many times patients are not candidates for a second or third redo operation due to progressive underlying frailty. This unmet patient need required the creative thinking of placing off-label occluder devices at the site of surgical valve failure. Simple in concept, these highly complex procedural cases five years prior would average five to seven hours in duration. However, patient-specific anatomy can now better be understood through 3-D printing and computer simulation, constructing 3-D patient-specific models to accurately predict device sizing as well as device interaction with adjacent anatomical landmarks (Figure 2 below).[9,10]

In paravalvular leak closure cases, for instance, the use of 3-D models can decrease the total procedural time by up to a half. Such 3-D models are constructed from previously acquired imaging studies of the structure of interest (typically CT) and contribute significantly to the pre-planning phase of complex structural interventions.

Another helpful application of interventional imaging in the catheterization labs includes fusion imaging, whereby cardiac CT or TEE images are used to overlay anatomical markers on fluoroscopy screens to provide additional guidance for the implanting interventional cardiologist.[11]

4. Procedural Guidance

Interventional imagers play a critical role in the cardiac catheterization lab during structural interventions. Interventional Imagers need to be familiar with the cardiac catheterization lab and hybrid operating room set-up, personnel, and workflow. In addition, they need to be able to identify a multitude of wires, catheters, delivery systems and devices, which have diverse imaging profiles and effects on image quality. To successfully guide a structural intervention, part of their skillset includes acquiring in-depth knowledge of the different fluoroscopic projections and details of the procedural steps. A thorough understanding of the patient’s unique pathology, surrounding anatomic structures and the real-time interaction of the delivery system and device within this environment is required.

One of the most important skills for interventional imagers is mastering the language of a structural intervention and effectively communicating with the team. In order to safely guide an intervention, it is essential that they communicate clearly, confidently and in a timely manner. For instance, by acquiring live 2-D and 3-D TEE images throughout the course of a MitraClip intervention, interventional imagers confirm the ideal transseptal puncture site, comment on the trajectory of delivery systems, guide positioning of the MitraClip device and confirm adequate leaflet grasping (Figure 3 below).

Acquiring real-time, high-quality 3-D images is critical in all these steps. During and after successful device deployment, interventional imagers incorporate objective echocardiographic, fluoroscopic, and hemodynamic data to assess residual mitral regurgitation and the need for additional clips. Such skills are similarly critical in other procedures such as left atrial appendage (LAA) occlusion, transcatheter mitral valve replacement (TMVR) (Figure 4 below), and paravalvular leak closure, among others.

Interventional imagers need to be able to quickly recognize any immediate procedural complications and communicate them to the team without delay. This requires their constant and undivided attention during lengthy procedures. These complications include the development of hemodynamically significant pericardial effusions, device instability and paravalvular regurgitation.

5. Follow-up

The interventional imagers’ job does not end at procedure completion. Clinical and imaging follow-up of patients is part of their key responsibilities. They evaluate patients on an outpatient basis and review their follow-up imaging studies. For example, in patients who undergo TAVR, this includes assessment of prosthesis gradient, the presence of paravalvular regurgitation and potentially the presence of hypo-attenuation leaflet thickening (HALT) with post-TAVR CTA. In patients with evidence of significant prosthetic valve obstruction or paravalvular regurgitation, a detailed cardiac CT study allows for planning of valve-in-valve interventions or paravalvular leak closure.

Career Challenges for Interventional Imagers

Despite the clear role that Interventional Imagers play in complex and delicate high-risk structural procedures, yet they face the following key challenges:

1. Inadequate Reimbursement

Existing reimbursement models do not offer adequate compensation to interventional imagers. Pre-procedural planning is time-consuming and entails special expertise and skills in 3-D reconstruction. Despite the significance of the pre-procedural imaging steps in optimizing outcomes and preventing complications, this is not part of the reimbursement model for a structural intervention. Some structural heart procedures can be lengthy, and therefore generating disproportionately low relative value units (RVU). In addition, there remains a clear discrepancy between payment models for interventional imagers compared to interventional cardiologists, despite their respective roles as co-operators in procedures such as transcatheter mitral valve repair with MitraClip device.

2. Lack of Dedicated Interventional Imaging Training and Mentorship

Despite the necessary expertise and invaluable skillset needed to master the field of interventional imaging, only a few dedicated training programs exist to train the future generation of Interventional Imagers. In addition, there are no clearly defined training requirements yet for this unique subspecialty by the Core Cardiovascular Training Statement (COCATS). Recognition of the field of interventional imaging as a subspecialty of cardiac imaging by different societies is of paramount importance in advancing this field and creating formalized training programs.

3. Health Hazards

The interventional imager is usually positioned to the left side of the patient where radiation safety measures are not typically constructed in the cath lab for their protection. This, coupled with lengthy procedures, increases the interventional imager’s exposure to radiation and its consequences. A recent study actually showed that interventional imagers are exposed to a radiation dose at least as high as that to which a primary operator is exposed.[12] Additionally, prolonged procedures combined with heavy lead suits lead to significant repetitive motion injury and physical stress.

Conclusion

Interventional imagers are fundamental for the success of a heart team and structural heart program. As the landscape of SHD interventions evolves to include patients with more diverse indications and lower surgical risk, emphasis needs to be placed on advocating for highly skilled, appropriately trained interventional imagers with a sustainable, appropriate compensation. This recognition is of utmost significance for the continued growth of the field, and for the procedural success. Above all, the needs of patients remain the primary target of heart teams and patients will directly benefit from their journey to recovery being led by the most skilled orchestrators.

Editor’s note: The authors of this article include:

Nadeen N. Faza, M.D., advanced cardiac imaging fellow, Houston Methodist HospitalHouston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center, Department of Cardiology, Houston Methodist Hospital, Texas.

Dee Dee Wang, M.D., director, structural heart imaging, Center for Structural Heart Disease, Division of Cardiology, Henry Ford Health System, Detroit, Mich.

Joao Cavalcante, M.D., director, cardiac MR and structural CT labs, Valve Science Center, Minneapolis Heart Institute Foundation.

Andrew D. Choi, M.D., Division of Cardiology and Department of Radiology, The George Washington University School of Medicine, Washington, DC 4;

Stephen H. Little, M.D., Houston Methodist DeBakey Heart and Vascular Center, Department of Cardiology, Houston Methodist Hospital, Texas

Related Interventional Imaging Content:

References:

July 23, 2024

July 23, 2024