November 22, 2010 – At the VEITHsymposium, physicians debated whether stents are usually required in the endovenous treatment of chronic venous disease.

Seshadri Raju M.D., professor emeritus of surgery at the University of Mississippi Medical Center in Flowood, Miss., said that detectable iliac vein stenosis is present in more than 90 percent of cases of chronic venous disease (CVD).

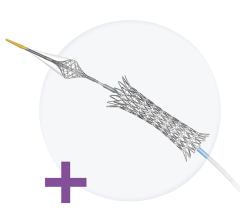

He said that in about a third of cases, the obstruction is the sole pathology. In the other two-thirds, associated reflux is present, making it difficult to diagnose iliac vein obstruction. Stent technology has made it easier to correct the obstructive component. Nearly 75 percent of patients report significant improvement in limb pain, and roughly two-thirds of patients are completely relieved of pain over five years. Frequent usage of stenting has resulted in a near total endovenous practice with a radical decline in the need for open surgery.

But Gregory L. Moneta, M.D., chief professor of surgery at the division of vascular surgery at Oregon Health and Science University disagrees.

“For now, stents are best avoided in the endovascular treatment of venous disease,” he said. “However, some perspective is in order. The surgeons in Jackson are now telling us that, after years of previously telling us we need to correct venous reflux, all of a sudden, deep and saphenous reflux is not really important. After years of telling us we need to carefully evaluate venous hemodynamics all of a sudden venous hemodynamics do not matter—only IVUS (intravascular ultrasound) images matter. We are being asked to completely reassess our concepts of venous pathophysiology, our ability to quantify perturbations of venous physiology and our treatments for chronic venous disease, and adopt and widely utilize very expensive technology.”

According to Moneta, use of stents in the venous system has, of late, received a great deal of publicity with no convincing evidence that they are required to facilitate favorable outcomes in patients with venous disorders.

Surgeons from Jackson, Miss., drew the following conclusions:

• Venous stenting results in “major symptom relief in patients with chronic venous disease. However, there is no consistently reflected hemodynamic improvement reflected by conventional measurement.

• Iliac venous stenting alone is sufficient to control symptoms in the majority of patients with combined outflow obstruction and deep reflux.

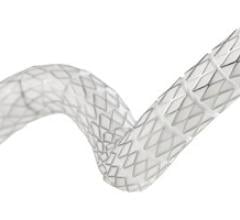

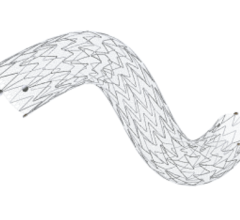

• Venous stents can be safely placed in the venous system across the inguinal crease with no risk of stent fractures, narrowing due to external compression, focal development of severe in-stent re-stenosis and no effect on long term patency.

“There is nothing wrong with reassessing old concepts; that is one of the things facilitating progress,” Moneta said. “On the other hand, data that comes primarily from a single center, by unblinded observer, with a financial interest in the procedures they are advocating, cannot serve as justification for a complete change in concept of treatment of venous disease no matter how much we respect these observers, their contributions to the venous literature, and no matter how much we would like to believe that the data from Jackson can extrapolated to those of us practicing in other locations.”

“To adopt the practice pattern of widespread venous stenting and totally change established concepts of chronic venous disease, we need to be guided by blinded, clearly unbiased observers level 1 data of efficacy for patient oriented outcomes that matter. This must be in the context of a proper randomized trial,” Moneta said. “We also need cost data, effectiveness data and an analysis of the potential impact on the health care system. Only then will we will be able to properly evaluate the role of stents in the treatment of venous disease.”

For more information: www.VEITHpress.org

November 24, 2025

November 24, 2025