March 31, 2008 - New evidence from a large randomized study is answering important questions about the best approach to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in patients with a type of heart attack known as ST-segment-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI). In the study, drug-eluting stents outperformed bare-metal stents, and high-dose tirofiban, an anti-clotting medication, proved to be equally effective and have fewer side effects than the catheter lab standard, abciximab.

The study is being reported today in a Late-Breaking Clinical Trials session at the SCAI Annual Scientific Sessions in Partnership with ACC i2 Summit (SCAI-ACCi2) in Chicago. SCAI-ACCi2 is a scientific meeting for practicing cardiovascular interventionalists sponsored by the Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions (SCAI) in partnership with the American College of Cardiology (ACC). This study is also being simultaneously published online in JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association.

“These findings may provide a robust scientific rationale for high-dose tirofiban as an alternative to abciximab in patients with STEMI,” said Marco Valgimigli, MD, PhD, a cardiologist at the Cardiovascular Institute, Azienda Opedaliera Universitaria di Ferrara, Ferrara, Italy. “In addition, at mid- term follow-up our study did not confirm some of the safety concerns over the use of drug-eluting stents in patients with myocardial infarction. These findings are very reassuring, though we need long-term follow-up to rule out the possibility of late adverse events.”

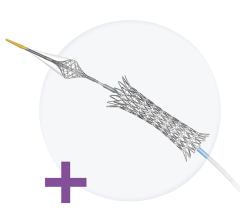

Drug-eluting stents—which not only prop open the coronary arteries but slowly release medication that prevents re-narrowing of the arteries with scar tissue, or restenosis—are widely used when PCI is performed for stable coronary artery disease. But many cardiologists use bare-metal stents when treating patients with heart attack because studies have reported conflicting results on the benefits of drug-eluting stents in this group of patients and have raised concerns over the risk of blood clotting inside the stent, or stent thrombosis. The new study has certain design advantages over previous studies, specifically its size and an enrollment and follow-up protocol that more closely reflects everyday clinical practice.

As for tirofiban and abciximab, both are in a class of medications known as glycoprotein 2b/3a inhibitors and prevent blood clotting by blocking hyperactivation of platelets. Tirofiban is an attractive alternative for several reasons: It is shorter-acting and is cleared from the body more readily than abciximab, it is less likely to cause a dangerous drop in the number of platelets in the blood, and it is far less expensive. However, previous studies have been too small or have used too low a dose of tirofiban to reach a definitive conclusion about which medication is better, Dr. Valgimigli said.

The new study, which involved 16 medical centers, enrolled 745 patients who were set to undergo PCI for STEMI. Patients were randomly assigned to an infusion of abciximab or high-dose tirofiban (25 _g/kg) and, in a second round of randomization, to treatment with either uncoated or sirolimus-eluting stents.

To judge the effectiveness of tirofiban and abciximab, researchers examined electrocardiograms—722 of which were interpretable—to determine the proportion of patients with at least a 50 percent return of the elevated “ST-segment” to its normal baseline. The results were equivalent in the two groups (83.6 percent in the abciximab group vs. 85.3 percent in the tirofiban group). In addition, there was no significant difference in the rate of major adverse cardiac events (MACE)—a combination of death, repeat heart attack, and repeat procedure to open the treated coronary artery—in the two groups: 4.8 percent vs. 4.5 percent, respectively, at 30 days and 12.3 percent vs. 9.9 percent, respectively, at eight months. The rates of minor and major bleeding did not differ in the two groups, but a marked drop in the blood platelet count—a complication that could cause uncontrolled bleeding—was more common among patients treated with abciximab (4.0 percent vs. 0.8 percent, p=0.004).

When comparing the two types of stents, investigators found an equivalent MACE rate at 30 days (3.9 percent vs. 5.9 percent, p=0.12) with sirolimus-eluting and bare-metal stents. However, at eight months, the MACE rate was significantly lower with drug-eluting stents (7.8 percent vs. 14.5 percent, p=0.0039). This difference was mainly driven by a 69 percent reduction in the need for a repeat procedure to reopen the treated coronary artery (3.2 percent with sirolimus-eluting stents vs. 10.2 percent with bare- metal stents, p=0.0004). The rates of death and repeat heart attack were similar, as was the incidence of stent thrombosis.

“Our study shows that tirofiban is ‘noninferior’ in its efficacy to abciximab in this high-risk patient population, and has a better safety profile,” said Dr. Valgimigli. “We have also confirmed that, even in STEMI patients, drug-eluting stents are highly effective in reducing reintervention in the target vessel. More important, this came without an extra price to pay in terms of death, myocardial infarction or stent thrombosis.”

Dr. Valgimigli will present the results of this study on Sunday, March 30 at 9:00 a.m. CDT in the Grand Ballroom, S100. This study will simultaneously publish in JAMA: Journal of the American Medical Association.

For more information: www.acc08.org

November 24, 2025

November 24, 2025