While reinforcing the importance of treating all known risk factors that contribute to atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, ASCVD, physicians also need to recognize and treat systemic inflammation in CV disease, according to the author who addresses the importance of identifying and reducing residual inflammatory risk.

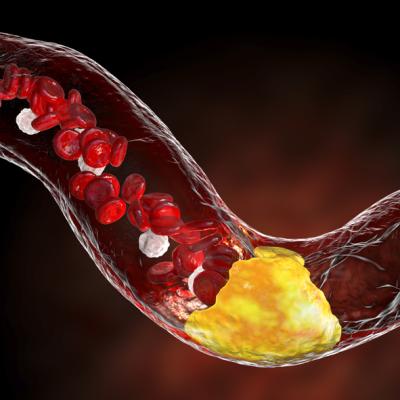

Atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD), caused by plaque buildup in arterial walls, is one of the leading causes of disability and death worldwide.1,2 ASCVD causes or contributes to conditions that include coronary artery disease (CAD), cerebrovascular disease, and peripheral vascular disease (inclusive of aortic aneurysm).3

Patients with ASCVD are at a higher risk for major adverse cardiovascular events (MACE) including heart attack or myocardial infarction (MI), stroke, and cardiovascular (CV) death.4 In the U.S. alone, more than 800,000 of these people are at risk of MI and for approximately 200,000 of them, this may well be their second life-threatening cardiac event. Nearly 20% of those people who have had a MI will be hospitalized again within five years due to a second event.5

Over my career as a cardiovascular surgeon, as well as an immunologist, I have witnessed how current treatments for ASCVD have led to considerable improvements in outcomes, yet many patients remain vulnerable to life-threatening cardiac events.1,6 Until recently atherosclerosis has been thought of as the result of passive lipid accumulation in the vessel wall. However, the development of atherosclerosis is now known to be much more complex, with a key role for immune cells and inflammation in conjunction with hyperlipidemia and elevated LDL levels.7

Research has shown inflammation plays a significant role in the development of atherosclerosis and ASCVD,8-10 and even the formation of plaque.11 Despite the link between inflammation and cardiovascular disease has been proven by extensive research, most physicians have focused on treating high-risk patients with lipid lowering therapies including statin therapy.1,12,13

While it is important to treat all known risk factors that contribute to ASCVD including high blood pressure, hyperlipidemia, diabetes, and obesity, physicians also need to recognize and treat systemic inflammation in CV disease.

Importance of Residual Inflammatory Risk

Residual inflammatory risk refers to the risk of a patient having a heart attack, stroke or further CV problems due to underlying persistent inflammation. Historically I have witnessed patients with systemic inflammatory disorders, and I know how they affect the cardiovascular system.

Inflammation driven by signaling cytokines, circulating immune cells, adhesion molecules, and oxidized low-density lipoprotein cholesterol (LDL-C) leads to atherosclerotic plaque development, plaque progression, and eventual rupture.14,15 Similarly, the NLRP3 inflammasome has been implicated in pathogenesis as it leads to the activation of proinflammatory cytokines triggering robust proinflammatory signaling through interleukin-6 (IL-6) and inducing production of C-reactive protein (CRP), a biomarker for inflammation.16 Left untreated over time, this inflammation can increase a patient's likelihood of a life-threatening cardiac event.

Clinically, I have observed patients with various systemic inflammatory disorders including psoriatic disease or psoriasis, rheumatoid arthritis and systemic lupus erythematosus (SLE) and although each of these diseases are very different from one another, all have been linked to an increased risk of atherosclerosis.17-19 Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory disease of the skin and joints that affects two to three percent of the world's population and has been clearly linked to multiple associated comorbidities including an increased prevalence of CV risk factors.17

I have also seen the cardiovascular effects from rheumatoid arthritis (RA), an autoimmune disease that predominately affects the joints. These patients have an increased mortality rate due to CV events and, more notably, women living with RA have a twofold to threefold increased risk of heart attack even without the traditional cardiovascular risk factors.18

Lastly with SLE, despite most patients living with SLE being young females, who are not classically considered to be at high risk for CV disease, these patients have a strong risk of CV events compared to the general population.19 As such, it is important that physicians who treat patients with autoimmune conditions, including dermatologists and rheumatologists, recognize that these diseases predispose patients to CV disease and take steps to ensure their patients get the best treatment possible to improve outcomes.

Clinical Trials Support Impact of Inflammation Inhibition

Recently, major cardiovascular clinical trials have shown that aggressive inhibition of inflammation is a crucial therapeutic target for secondary prevention in high-risk patients.12,16 In 2017, CANTOS (Canakinumab Anti-inflammatory Thrombosis Outcomes Study) provided proof-of-principle that inflammation inhibition in the absence of lipid lowering can significantly reduce cardiovascular event rates and helped to define the interleukin-1 (IL-1) to IL-6 to CRP pathway as a central target in CV disease.16

In the study, more than 10,000 patients who had stable atherosclerosis with residual inflammatory risk and were already on statin therapy were randomized to receive placebo or two different doses of canakinumab, 150 mg or 300 mg. Those allocated to higher doses of canakinumab, a monoclonal antibody that binds IL-1β, experienced a 15% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events and a 17% reduction in major adverse cardiovascular events plus urgent revascularization in comparison with placebo.20

More recently, a collaborative analysis was performed on participants in one of three major multinational trials (PROMINENT, REDUCE-IT, and STRENGTH) with or at high-risk of atherosclerotic disease who were receiving contemporary statins. In the study which included 31,245 patients, residual inflammatory risk was found to be a more powerful determinant of recurrent cardiovascular events, cardiovascular death, and all-cause mortality than by LDL-C. These data suggest that inflammation-inhibiting therapies along with aggressive lipid-lowering medications might be needed to further reduce atherosclerotic risk.21

Measuring Residual Inflammatory Risk

For physicians to effectively treat cardiovascular disease, it’s necessary to address both cholesterol risk and residual inflammatory risk to reduce the risk of a heart attack or stroke in patients.21 Luckily, each of these risks can be measured by simple blood tests. Still, although many patients and practitioners are aware of blood tests measuring LDL-C to predict CV risk, fewer know or recognize the value of measuring residual inflammatory risk.

For most patients we can use high sensitivity C-reactive protein (hsCRP) to determine residual inflammatory risk.21-23 hsCRP is nonspecific inflammatory marker and an acute phase reactant that predicts the likelihood of a heart attack, stroke, peripheral artery disease and sudden cardiac death among healthy individuals with no history of CV disease, and recurrent events and death in patients with known ASCVD.22

In general, hsCRP values above 2.0 milligrams per liter (mg/L) are linked to increased risk of heart attacks or risk of a repeat heart attack.23 Still, an hsCRP test should not be confused with a CRP test which measures the level of CRP in your blood. An hsCRP test is more sensitive and can find smaller increases in CRP than a standard test can.23

It is important to remember that a person’s hsCRP level varies over time and a coronary artery disease risk assessment should be based on the average of two hsCRP tests.23 For hsCRP, when values are very high (above 10 mg/L) it’s likely that the body is responding to a cold or infectious disease and so another test should be performed to confirm the biomarker.23 The utility of hsCRP to predict high CV risk in secondary prevention parallels studies of hsCRP in primary prevention published more than 20 years ago.24,25 Among statin-treated patients with hsCRP greater than 2 mg/L, risks for cardiovascular death were high regardless of LDL-C level.21

Clinicians beyond those in the field of cardiology should measure hsCRP as an indication of residual inflammatory risk to understand the underlying biological factors facing patients and to determine which patients may benefit from the addition of an anti-inflammatory medication.

Almost half of all patients on aggressive statin therapy have residual inflammatory risk.26 Similarly, over one-third of ASCVD patients have hsCRP levels above 2 mg/L which indicates a higher risk of heart disease.12,27 In contemporary lipid-lowering trials, there are roughly twice as many individuals in whom the principle unmet clinical need is residual inflammatory risk as compared with residual cholesterol risk.28 As such, targeting inflammation in the context of cardiovascular disease is of the utmost importance for me and any impacted patients.

Targeting & Treating Inflammation Underlying ASCVD

With this mountain of evidence demonstrating the role of inflammation in CVD, last year the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) approved the first anti-inflammatory therapeutic option to reduce cardiac event risk in patients with established cardiac risk factors. The repurposed drug is safe, cost-effective and efficacious.

As of June 2023, the U.S. FDA approved LODOCO (colchicine, 0.5 mg) to reduce the risks of heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization, and CV death.29 Colchicine reduces multiple pro-inflammatory mechanisms and has been shown to inhibit the migration and chemotaxis of neutrophils to inflamed areas and to decrease adhesion of neutrophils to inflamed endothelium by decreasing expression of L-selectin adhesion molecules.30-33

Consistent with these findings and although the precise mechanism remains poorly understood, colchicine may suppress the assembly and activation of the NLRP3 inflammasome, with an indirect decrease in inflammasome-mediated production of IL-1β and IL-18. This in turn leads to an overall reduction in IL-6 production and CRP concentration.12

Colchicine, 0.5 mg has been shown to safely lower MACE by 31% among those with stable atherosclerosis34 and by 23% after recent heart attack compared to placebo and on top of standard-of-care including statin therapy.35 In a large multicenter double-blind randomized trial (LoDoCo2) involving 5,522 patients with clinically stable coronary artery disease, almost all of them on statin therapy, colchicine, 0.5 mg reduced the risk of cardiovascular death, MI or heart attack, ischemic stroke, or ischemia-driven coronary revascularization by 31% compared with placebo.34

Colchicine, 0.5 mg also showed clinical benefits in patients following a recent MI (COLCOT trial). In a double-blind, placebo-controlled study in 4,745 patients who had suffered a heart attack within 30 days showed over a median follow-up of 23 months, patients treated with colchicine, 0.5 mg experienced a 23% lower incidence of death from cardiovascular causes, resuscitated cardiac arrest, myocardial infarction, stroke, or urgent hospitalization for angina leading to coronary revascularization in a time-to-event analysis. The benefit was most significant in reducing the incidence of stroke and angina requiring revascularization.35

Overall, the magnitudes of benefit seen from colchicine, 0.5 mg are larger than those seen in contemporary secondary prevention trials of adjunctive lipid-lowering agents.12 Importantly, colchicine, 0.5 mg is associated with a 30–40% reduction in median hsCRP levels and a 16% reduction in median IL-6 levels in patients with chronic coronary disease.33,36,37

Colchicine, 0.5 mg has been proven to be safe and effective in patients taking high-intensity statins and in clinical studies myotoxicity was reported at the same rate in those treated with colchicine or placebo.34,35 In clinical trials, more than 96% of the patients received low-dose colchicine in addition to high intensity statin therapy. Even so, the most common adverse events in patients treated with colchicine are diarrhea, nausea, and abdominal pain in up to 10% of those initiating therapy.34,35

In the LoDoCo 2 trial, similar rates of patients in each treatment group (10.5%) permanently discontinued either colchicine or placebo prematurely due to gastrointestinal upset. For most individuals, these gastrointestinal effects markedly attenuate with longer-term therapy.34 The safety of colchicine, 0.5 mg is highly reassuring and there were no excess of cases of statin-associated myopathy in more than 10,000 statin-treated patients in clinical trials.12

However, it is important to note that colchicine should not be prescribed to individuals with clinically significant chronic kidney disease or hepatic dysfunction and should not be used in combination with strong inhibitors of CYP3A4 or P-glycoprotein, such as clarithromycin, azole antifungal agents, and certain immunosuppressive medications should be avoided in patients on colchicine.12,29,38 Colchicine should be temporarily discontinued for a week or two if any of these drugs are initiated as short-term therapy.38 Even with mild renal impairment, some people can exceed the upper safety limit of 3.0 μ/L on 0.6 mg. colchicine which poses the greatest risk among patients 65 or older who may have declining liver or kidney function.38

Conclusion

Substantial progress has been made in preventing heart attacks or stroke in patients. As of last year in the U.S., physicians now have a medication that can address systemic inflammation as an underlying, contributing factor to ASCVD and significantly lower the likelihood of life-threatening events in patients. The best care for most atherosclerosis patients is likely to include combined use of aggressive LDL-C-lowering and inflammation-inhibiting therapies as targeting LDL-C is unlikely to eliminate ASCVD risk alone.

For physicians, it is important to recognize the importance of inflammation and measure an hsCRP level to determine which next steps should be taken to address a patient’s residual risk. This can determine if an anti-inflammatory therapy may be necessary to lower the likelihood of heart attack and stroke. The recent FDA approval of LODOCO tablets, which may be used alone or in combination with a patient’s current lipid-lowering medication, can help clinicians, including myself, effectively treat cardiovascular disease by now addressing residual inflammatory risk to reduce the risk of a heart attack or stroke.

Robert L. Quigley, MD, DPhil, is an international healthcare consultant and a senior consultant for International SOS. He is the co-founder and executive chairman of the International Corporate Health Leadership Council (ICHLC), a 501(c) (6) organization. He formerly served as senior vice president and global medical director, corporate health solutions, at International SOS Assistance & MedAire, Americas Region, and was responsible for leading the delivery of high-quality medical assistance, healthcare management, and medical transportation services. Prior to joining International SOS, Quigley was a triple board re-certified cardiovascular and thoracic surgeon who directed two open heart programs within the Jefferson Health System (Phil., PA), where he was a professor of surgery at Jefferson Medical College. He holds a doctorate in immunology.

References:

1. Arnett DK, Blumenthal RS, Albert MA, et al. 2019 ACC/AHA Guideline on the Primary Prevention of Cardiovascular Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines [published correction appears in Circulation. 2019 Sep 10;140(11):e649-e650] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2020 Jan 28;141(4):e60] [published correction appears in Circulation. 2020 Apr 21;141(16):e774]. Circulation. 2019;140(11):e596-e646. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000000678

2. Roth GA, Mensah GA, Johnson CO, et al. Global Burden of Cardiovascular Diseases and Risk Factors, 1990-2019: Update From the GBD 2019 Study [published correction appears in J Am Coll Cardiol. 2021 Apr 20;77(15):1958-1959]. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;76(25):2982-3021. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2020.11.010

3. ASCVD. American Heart Association. Accessed November 8, 2023. https://www.heart.org/en/professional/quality-improvement/ascvd

4. Miao B, Hernandez AV, Alberts MJ, Mangiafico N, Roman YM, Coleman CI. Incidence and Predictors of Major Adverse Cardiovascular Events in Patients With Established Atherosclerotic Disease or Multiple Risk Factors. J Am Heart Assoc. 2020;9(2):e014402. doi:10.1161/JAHA.119.014402

5. Tsao CW, Aday AW, Almarzooq ZI, et al. Heart Disease and Stroke Statistics-2022 Update: A Report From the American Heart Association [published correction appears in Circulation. 2022 Sep 6;146(10):e141]. Circulation. 2022;145(8):e153-e639. doi:10.1161/CIR.0000000000001052

6. Makover ME, Shapiro MD, Toth PP. There is urgent need to treat atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease risk earlier, more intensively, and with greater precision: A review of current practice and recommendations for improved effectiveness. Am J Prev Cardiol. 2022;12:100371. Published 2022 Aug 6. doi:10.1016/j.ajpc.2022.100371

7. Schaftenaar F, Frodermann V, Kuiper J, Lutgens E. Atherosclerosis: the interplay between lipids and immune cells. Curr Opin Lipidol. 2016;27(3):209-215. doi:10.1097/MOL.0000000000000302

8. Ross R. Atherosclerosis--an inflammatory disease. N Engl J Med. 1999;340(2):115-126. doi:10.1056/NEJM199901143400207

9. Hansson GK. Inflammation, atherosclerosis, and coronary artery disease. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(16):1685-1695. doi:10.1056/NEJMra043430

10. Libby P. Mechanisms of acute coronary syndromes and their implications for therapy. N Engl J Med. 2013;368(21):2004-2013. doi:10.1056/NEJMra1216063

11. Christodoulidis G, Vittorio TJ, Fudim M, Lerakis S, Kosmas CE. Inflammation in coronary artery disease. Cardiol Rev. 2014;22(6):279-288. doi:10.1097/CRD.0000000000000006

12. Nelson K, Fuster V, Ridker PM. Low-Dose Colchicine for Secondary Prevention of Coronary Artery Disease: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2023;82(7):648-660. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2023.05.055

13. Aday AW, Ridker PM. Targeting Residual Inflammatory Risk: A Shifting Paradigm for Atherosclerotic Disease. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2019;6:16. Published 2019 Feb 28. doi:10.3389/fcvm.2019.00016

14. Ridker PM. Anti- inflammatory Therapy for Cardiovascular Disease. In: Ballantyne CM, ed. Clinical Lipidology: A Companion to Braunwald’s Heart Disease. 3rd Edition. Elsevier; 2024:224-235.

15. Fava C, Montagnana M. Atherosclerosis Is an Inflammatory Disease which Lacks a Common Anti-inflammatory Therapy: How Human Genetics Can Help to This Issue. A Narrative Review. Front Pharmacol. 2018;9:55. Published 2018 Feb 6. doi:10.3389/fphar.2018.00055

16. Ridker PM. From CANTOS to CIRT to COLCOT to Clinic: Will All Atherosclerosis Patients Soon Be Treated With Combination Lipid-Lowering and Inflammation-Inhibiting Agents?. Circulation. 2020;141(10):787-789. doi:10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.119.045256

17. Armstrong EJ, Harskamp CT, Armstrong AW. Psoriasis and major adverse cardiovascular events: a systematic review and meta-analysis of observational studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2013;2(2):e000062. Published 2013 Apr 4. doi:10.1161/JAHA.113.000062

19. Tobin R, Patel N, Tobb K, Weber B, Mehta PK, Isiadinso I. Atherosclerosis in Systemic Lupus Erythematosus. Curr Atheroscler Rep. 2023;25(11):819-827. doi:10.1007/s11883-023-01149-4

20. Ridker PM, Everett BM, Thuren T, et al. Antiinflammatory Therapy with Canakinumab for Atherosclerotic Disease. N Engl J Med. 2017;377(12):1119-1131. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1707914

21. Ridker PM, Bhatt DL, Pradhan AD, et al. Inflammation and cholesterol as predictors of cardiovascular events among patients receiving statin therapy: a collaborative analysis of three randomised trials. Lancet. 2023;401(10384):1293-1301. doi:10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00215-5

22. Bassuk SS, Rifai N, Ridker PM. High-sensitivity C-reactive protein: clinical importance. Curr Probl Cardiol. 2004;29(8):439-493.

23. C-Reactive Protein Test. Mayo Clinic. December 22, 2022. Accessed January 8, 2024. https://www.mayoclinic.org/tests-procedures/c-reactive-protein-test/about/pac-20385228.

24. Ridker P, Cushman M, Stampfer M, et al. Inflammation, aspirin, and the risk of cardiovascular disease in apparently healthy men. N Engl J Med. 1997;336:973–979.

25. Ridker P, Hennekens C, Buring J, et al. C Reactive protein and other markers of inflammation in the prediction of cardiovascular disease in women. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:836–843.

26. Ridker PM. Clinician's Guide to Reducing Inflammation to Reduce Atherothrombotic Risk: JACC Review Topic of the Week. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2018;72(25):3320-3331. doi:10.1016/j.jacc.2018.06.082

27. Do you know which blood tests can point to heart disease? Mayo Clinic. Published January 15, 2022. Accessed January 18, 2023. https://www.mayoclinic.org/diseases-conditions/heart-disease/in-depth/heart-disease/art-20049357

28. Ridker PM. How Common Is Residual Inflammatory Risk?. Circ Res. 2017;120(4):617-619. doi:10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.116.310527

29. LODOCO. Prescribing information. AGEPHA Pharma FZ LLC; 2023.

30. Leung YY, Yao Hui LL, Kraus VB. Colchicine–Update on mechanisms of action and therapeutic uses. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2015;45(3):341-350. doi:10.1016/j.semarthrit.2015.06.013

31. Zhang FS, He QZ, Qin CH, Little PJ, Weng JP, Xu SW. Therapeutic potential of colchicine in cardiovascular medicine: a pharmacological review. Acta Pharmacologica Sinica. 2022 Sep;43(9):2173-90.

32. Imazio M, Nidorf M. Colchicine and the heart. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(28):2745-2760. doi:10.1093/eurheartj/ehab221

33. Fiolet ATL, Opstal TSJ, Silvis MJM, Cornel JH, Mosterd A. Targeting residual inflammatory risk in coronary disease: to catch a monkey by its tail. Neth Heart J. 2022;30(1):25-37. doi:10.1007/s12471-021-01605-3

34. Nidorf SM, Fiolet ATL, Mosterd A, et al. Colchicine in Patients with Chronic Coronary Disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383(19):1838-1847. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa2021372

35. Tardif JC, Kouz S, Waters DD, et al. Efficacy and Safety of Low-Dose Colchicine after Myocardial Infarction. N Engl J Med. 2019;381(26):2497-2505. doi:10.1056/NEJMoa1912388

36. Fiolet ATL, Silvis MJM, Opstal TSJ, et al. Short-term effect of low-dose colchicine on inflammatory biomarkers, lipids, blood count and renal function in chronic coronary artery disease and elevated high-sensitivity C-reactive protein. PLoSONE. 2020;15:e237665.

37. Opstal TSJ, Hoogeveen RM, Fiolet ATL, et al. Colchicine attenuates inflammation beyond the inflammasome in chronic coronary artery disease: a LoDoCo2 proteomic substudy. Circulation. 2020;142:1996–8.

38. Robinson PC, Terkeltaub R, Pillinger MH, et al. Consensus Statement Regarding the Efficacy and Safety of Long-Term Low-Dose Colchicine in Gout and Cardiovascular Disease. Am J Med. 2022;135(1):32-38. doi:10.1016/j.amjmed.2021.07.025

Related content:

U.S. FDA Approves First Anti-Inflammatory Drug for Cardiovascular Disease

February 04, 2026

February 04, 2026