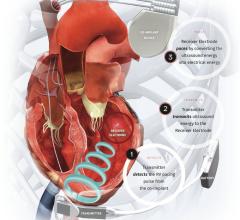

An implanted ICD showing its three leads in the venous system.

To extract or abandon broken or infected implantable, venous electrophysiology (EP) device leads has been a debate for more than 20 years. Some EPs argue there is a major risk to patients if old pacemaker or implantable cardioverter defibrillator (ICD) leads are extracted. Heavy scar tissue encases the leads after implant, and rough tugging to pull them out may cause the large veins to tear, which can be catastrophic. Supporters of lead extraction say it is necessary to remove the leads in many patients to prevent venous occlusion or the spread of infection.

In the past decade, the scales appear to be tipping in favor of lead extraction as the safety for the procedure improves. The Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) lead management guidelines updated most recently in 2017, along with new studies on lead extraction, have made many take a closer look at balancing risk versus benefit.

"A critical mass of people are becoming trained and comfortable with the idea, but it is a big investment," explained Bruce Wilkoff, M.D., FHRS, CCDS, director of cardiac pacing and tachyarrhythmia devices at Cleveland Clinic. He also served as the vice chair of the HRS expert consensus statement on cardiovascular implantable electronic device lead management and extraction.[1]

A Brief History of Lead Management

"We started doing lead extraction in the late 1980s, and at first it was just a few people trying to solve some problems, but a lot of people really just thought we were crazy," Wilkoff said.

He explained the first consensus document for lead management was created in the mid-1990s, but there were still few EPs who wanted to take on the potential patient safety risks. "In 2010, we re-did that consensus document, and by that time we had come to a point when we really had a community of people who accepted it as the thing to do, but no one was doing this in any volume. However, in the last five to six years it has really taken off. People are starting to become comfortable and they are willing to take on some risk to solve some important problems."

The biggest of these problems include lead infection, because it has an ongoing mortality risk. "We get the impression that infection is something you can cure with antibiotics, but it turns out subsequent 30, 60 and 90 days and subsequent year or two, you have ongoing mortality risk," Wilkoff said. "And if you don't take it out, infection will be universal. So, there is a mandate, you need to take it out when you have infection."

Infection is rare, only occurring in about 2 percent of patients who get an initial lead placement or an upgraded lead, he said, with infection more common with cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT).

Increasing Number of Leads in Patients is an Issue

An additional problem with it is faulty or broken leads. Over time, due to constant movement in the body, the wires inside the leads can break. EP devices are increasingly being placed in younger patients, and most leads will not last more than 10-20 years. Wilkoff also noted with an increased use of CRT, these devices require several leads, which becomes an issue with how much room there is in the venous system to put more hardware in later during a replacement.

"So, you have the issue with filling up the venous system with leads, broken leads and issues with venous occlusions, so these are issues we have to take care of," Wilkoff explained.

Creating a Lead Management Team

Once a center decides lead extraction is a service they want to offer, Wilkoff said it is not something an operator just does, they need training and they need to assemble a team.

"You have to understand the risks that are involved and it is a collaboration between the nurses, the anesthesiologist, the surgeon, the operator, the echocardiographer and the infectious disease expert," he explained. "There are a number of people you need to assemble as a team to work together."

Etiology of Lead Scarring

Soon after most leads are placed in patients there is usually some clotting that forms on them. Over time, this becomes firmer with fibrosis and might even have calcification. Scarring generally occurs any place where the lead touches the endothelium, either in the vein or in the heart.

"There is lead-to-lead scarring, so they become attached to each other, and there is lead-to-vein fibrosis, which becomes stiffer and stiffer over time," Wilkoff described.

Use of Lead Management Techniques

The goal of lead extraction procedures is to peel away that fibrosis without tearing the vein. Wilkoff said a cutting sheath is used to release the lead from scar tissue all the way to the heart before attempting to tug on it to pull it out of the body.

A stylet is used to increase the tensile strength of the lead so if you are pulling it from the outside, then the whole lead comes together so it does not stretch and pull apart.

The second tool is a set of telescoping sheaths. These have a hollow lumen and are placed over the lead, using a guidewire to follow the course of the lead and only cut the tissue that is immediately touching the lead. These come in a set of two flexible plastic sheaths that have a beveled cutting edge to separate the lead from the surrounding tissue using manual rotation of the sheath. Wilkoff said today, it is more common to see use of a mechanical version of this system, where a small, circular, rotary cutting blade is actuated with a pistol grip trigger mechanism. These devices are offered by Cook Medical and Spectranetics, which is now part of Philips Healthcare.

Spectranetics also has an FDA-cleared excimer laser sheath system to cut through tissue to release the leads.

Potential Complications of Electrophysiology Device Lead Extraction

One of the biggest safety concerns in removing old device leads is the possibility of tearing the superior vena cava (SVC). This requires immediate emergency surgical repair to stop the bleeding and the complication currently has a 50 percent mortality rate.

"Most of the time lead extraction works out really well, and in 98 percent of cases there are no major complications," Wilkoff said. "But, in the 1.5 to 2 percent range there can be a tear to the venous system or the heart and cause a surgical emergency."

Unfortunately, he said, you cannot tell which patients will do well and which will not, so you always need to be ready. This is why it is so important to have clear coordination with an echocardiographer and a surgeon on a team in case there is tear that need immediate open surgical repair.

Increasing the Safety of Lead Extractions

The most serious location to get a tear is the SVC, Wilkoff explained. "A laceration in the SVC is what can cause the most problems," he stressed. "If it bleeds into the chest it will cause a hemothorax, or into the pericardium, causing a pericardial tamponade. If it starts bleeding there, it goes very quickly and opening up a person's chest in time is very difficult."

However, with the introduction of the Spectranetics Bridge Occlusion Balloon in 2016, the there is a new level of safety that can be achieved. It offers a safety net during procedures, allowing rapid inflation of an intravascular balloon to seal the tear and allow the surgical team time to prep and perform a repair without fear of the patient bleeding out. The device was credited with saving about 20 lives in the first year after gaining market clearance.

A guidewire is placed prior to the procedure through the femoral vein to the SVC. If needed, the balloon is advanced up the wire and is inflated using iodine contrast so it can clearly be seen on angiography. The balloon seals the tear and makes it much easier for the surgeon to see and make the repair.

Setting Standards for Lead Management Centers

Lead extraction procedures now number in the tens of thousands per year, but Wilkoff said standards need to be set. This is now included as part of the most recent 2017 revision of the HRS consensus document on lead management.

"Everybody should be able to tell their patients how many of these procedures they do, what their success rate is and what their complication rate is," Wilkoff said.

He noted the European Lead Extraction ConTRolled (ELECTRa) registry showed performance of centers performing 30 or more extractions a year were better than centers performing fewer than 30 per year.[2] As with any procedure, the more a center does, the better they become, he explained. "Our previous estimates that 20 procedures a year was good might be too low, which tells us that people who want to do this really need to make a commitment to do this or don't do it at all," Wilkoff said.

New 2017 HRS Expert Consensus on Lead Management and Extraction

In September 2017, the HRS published an updated Expert Consensus Statement on Cardiovascular Implantable Electronic Device Lead Management and Extraction.[1]

It was developed in collaboration with the American College of Cardiology (ACC), American Heart Association (AHA), Asia Pacific Heart Rhythm Society (APHRS), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA), European Heart Rhythm Association (EHRA), Infectious Diseases Society of America (IDSA), Latin American Heart Rhythm Society (LAHRS), Pediatric and Congenital Electrophysiology Society (PACES) and Society of Thoracic Surgeons (STS). It is intended to help clinicians in their decision-making process for managing leads and builds on the 2009 Transvenous Lead Extraction: Heart Rhythm Society Expert Consensus on Facilities, Training, Indications and Patient Management document. It provides practical clinical guidance in the broad field of lead management, including lead extraction.

The document features a clinician summary and a pocket card. It is available across multiple platforms, including print, electronic media, and the Guideline Central mobile app at www.guidelinecentral.com.

The statement focuses on identifying the presence of lead malfunction, deciding on whether to abandon or to extract a lead that is no longer clinically necessary or at higher risk for failure, offering guidance on whether a cardiovascular implantable electronic device (CIED) is involved in an infectious process, providing recommendations on when lead extraction should be considered, and discussing specific clinical considerations for patient management when a lead extraction is performed.

The document includes specific recommendations in the following areas:

• Lead Survival

• Existing CIED Lead Management

• Indications for Lead Extraction (Infectious)

• Indications for Lead Extraction (Noninfectious)

• Outcomes and Follow-up

Expanding Lead Management Training via the Web

A few years ago, in an effort to expand lead extraction training to a greater audience, Wilkoff and others created an online group called LeadConnection.org. The goal was to reduce the economic barriers to getting training for EP operators who cannot attend the annual HRS or other larger EP meetings. The site includes a collection of all the literature on lead management, cases and offers a platform for sharing communication. The group also offers debates and webinars.

Related Lead Management Content:

Dr. Bruce Wilkoff Explains His Lead Management Learnings Over 20+ Years

Study Shows Occlusion Balloon Saves Lives During Lead Extraction

VIDEO: EP Lead Extraction Strategies — Interview with Bruce Wilkoff, M.D.

VIDEO: Demonstration of How the Bridge Occlusion Balloon Seals SVC Tears

Advances in Transvenous Lead Extraction — Article by Avi Fischer, M.D., FACC, FHRS

Strategies, New Technologies Aid Lead Management.

References:

July 21, 2025

July 21, 2025