The transcatheter MitraClip mitral valve repair system continues to compare favorably with conventional open-heart surgery for treatment of select patients with mitral regurgitation. The findings come from updated research from the EVEREST II study presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 60th Annual Scientific Session.

Mitral regurgitation (MR) is common in aging hearts, appearing in 20 percent of echocardiograms for people older than 55. A loosely closing mitral valve leaks blood back into the heart, which responds by trying to pump harder. MR is progressive, and over time the overworked heart enlarges and weakens. Each year 250,000 people in the United States learn they have MR, but only 20 percent eventually undergo standard treatment to repair or replace the valve, which is open-heart surgery that puts patients on a heart-lung bypass machine. For many, that procedure poses too great a risk. Instead they rely on medications to reduce MR symptoms, and limit their activities as physical function declines. Symptoms of MR can include palpitations, shortness of breath, fatigue, lightheadedness, cough and swelling in the legs and feet from fluid buildup.

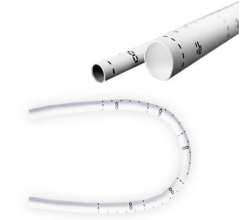

The percutaneous MitraClip involves a minimally invasive procedure that may make valve repair feasible for more people with MR. Cardiologists trained to use this system guide a catheter-mounted device through an incision in the groin, into the femoral artery and on to the heart. When the device is properly placed, it clamps the edges of the faulty valve together like a clothespin. Sometimes a second clip is inserted for better control of MR. Standard MR surgery and device insertion both take about two hours, but their hospitalization and recovery times differ greatly.

“After getting a MitraClip, patients spend one or two nights in the hospital versus five to seven days after open-heart surgery, and they’re back to full activity immediately,” said Ted Feldman, M.D., director of the cardiac catheterization laboratory at NorthShore University HealthSystem, Evanston, Ill., and the study’s co-principal investigator. “Traditional open-heart surgery has a recovery time of one to three months. The contrast is pretty striking.”

This phase II study enrolled 279 patients in 37 North American centers who met criteria for mitral valve surgery: grade 3+ (moderate to severe) or 4+ (severe) MR. All patients had valve anatomy suitable for the procedure and were randomly assigned in a 2-to-1 ratio to the MitraClip or to standard surgery. Both groups were well matched for baseline patient characteristics. Year one data have been published. This presentation reports year two data and patients will be followed for five years.

The effectiveness of the two treatments was measured by a composite of freedom from death, no new mitral valve surgery and MR lower than pretreatment minimum of 3+. In the treatment comparison, 101 patients (62.7 percent) in the percutaneous group met the composite endpoint vs. 66 (66.3 percent) in the surgery group. At two years, 78 percent of patients with the device did not need surgery.

Major adverse events at 30 days were significantly lower in the percutaneous group (15 percent vs. 47.9 percent). Blood transfusions of two units or more account for most of this difference: 13.3 percent in the percutaneous group vs. 44.7 percent for surgery patients.

Durability and anti-clotting drugs are other issues considered in this research. A mechanical heart valve lasts 35 years and requires the patient to take warfarin for life. Valve repair with a MitraClip should last approximately 15 years, and after implant, patients take clopidogrel for just one month and aspirin for six months. Although the procedure’s surgical version has demonstrated durability for more than 12 years, long-term outcomes from MitraClip can be defined only after further study.

“Both procedures reduced mitral regurgitation and produced meaningful clinical benefits, with the MitraClip valve repair increasing safety and surgery decreasing mitral regurgitation more completely,” Feldman said. “Our two-year data indicate that the percutaneous procedure is a therapeutic option for certain patients with significant mitral regurgitation.”

The EVEREST II study (Endovascular Valve Edge-to-Edge REpair STudy) is funded by Evalve, which also provides research funding to NorthShore University HealthSystem. Feldman is a consultant to Abbott, which acquired Evalve in 2009.

These findings will concurrently be published in the New England Journal of Medicine.

For more information: www.cardiosource.org

January 15, 2026

January 15, 2026