There is no consensus about whether atherosclerotic renal artery stenosis should be stented or treated medically. There are strong opinions on both sides and clinical data up to now is heavily debated. Many see the trials that could have answered this question as flawed. Those who see positive outcomes of renal stenting at high-volume centers say there is validity to stenting renals and the therapy has been unfairly condemned.

“There is really nothing wrong with renal stenting, as long as it is done by the right person in the right patient,” explained Christopher J. White, FAHA, FESC, professor of medicine, system chairman for cardiovascular diseases, The John Ochsner Heart and Vascular Institute, New Orleans. “Renal stenting works. I see it every day clinically. Renal stenting is life-saving and kidney-saving.”

Disputing Data from STAR, ASTRAL

The main issue has been the results of the European ASTRAL trial,1 released last fall, and the earlier STAR trial.2 Both compared medical treatment to stenting. Both showed poor outcomes for renal stenting and concluded it is ineffective. However, many critics who regularly stent renals say the trial data was based on small numbers of patients and the wrong patients, treated at centers inexperienced with renal stenting.

Critics of ASTRAL point to its enrollment of asymptomatic or minimally symptomatic patients with nonobstructive renal artery lesions (less than 70 percent stenosis). Many physicians said these are patients who are the least likely to benefit from revascularization. Critics also said ASTRAL and STAR were inconclusive because they were inadequately powered, had short followups, inconsistent use of stents and only enrolled mildly stenosed patients.

“I think the study authors really overreached in saying stenting is ineffective,” White said. “The question about how effective stenting is for the more severe lesions has not yet been answered.”

White said publishing data on mild patients and making a blanket statement about severe patients is a major disservice. He argues renal stenting is safe and effective in patients with severe renal stenosis.

White said ASTRAL’s results are correct for mildly symptomatic patients with 50 to 70 percent stenosis, but are very misleading for patients with severe stenosis. He argued that the trial inclusion criteria only included patients in which the physician was not sure if stenting would have an effect. As a result, White said patients with severe stenosis were excluded because they were referred for stents.

“The consequence was that no major lesions were treated,” White said. “You cannot make a mild artery better by putting a stent in it. That’s why we have guidelines.”

Another point White criticized about ASTRAL is that many of the participating centers only stented a couple of renal patients a year, so it is not surprising they had poor outcomes with 9 to 10 percent serious complication rates. He said that is a result of a lack of experience with renal stenting. White said experience is key to the success of any procedure. Ochsner stents 300 to 400 renal arteries a year, and that experience results in a 2 percent complication rate.

“If they don’t have the experience, maybe they shouldn’t be putting stents in people,” White said. “Renal stenting is not dangerous if it is done in competent hands. You need a risk-benefit analysis. Doctors need to think about who they are referring their patients to. Volume is a surrogate for quality.”

“I think there is validity for these concerns [about ASTRAL],” said Christopher J. Cooper, M.D., professor of medicine, chief, division of cardiovascular medicine, director of cardiovascular research at The University of Toledo Medical Center. He agrees that many of the patients in ASTRAL should not have been included because their condition did not merit treatment with a stent. He said 17 to 25 percent of patients in ASTRAL and STAR who were assigned stent treatment were found to have no significant stenosis, so they did not merit inclusion.

“It’s hard to show any therapy can help a condition if the patients you are treating don’t have the condition,” Cooper said.

If the patients who did not qualify for stenting were eliminated, he believes the trial would have shown a different outcome in favor of stents.

Drop in Stenting Referrals

After the results of ASTRAL were published last fall, there was a drop in renal stenting referrals across the country. Ochsner’s renal stenting volume dropped off significantly.

“A lot of internal medicine doctors read that and now don’t believe stenting will help their patients,” White said.

There is fear among many U.S. stenting advocates that more negative data based on poorly designed studies will be the final nail in the coffin of renal stenting.

The CORAL Trial

An ongoing study is designed to overcome many of the issues with STAR and ASTRAL and answer the question of stent efficacy and safety in patients with advanced renal stenosis. The Cardiovascular Outcomes in Renal Atherosclerotic Lesions (CORAL) study began in 2004. Its completion is expected in early 2014, with preliminary results expected in the fall of 2014.

CORAL closed enrollment in January 2010 with close to 950 patients. They either received blood pressure medication only, or blood pressure medication plus a renal stent. The trial is designed to look at long-term clinical outcomes.

Cooper, who is CORAL’s principal investigator, said a big criticism of the European trials was the lack of core labs, which are key parts of the current trial. These are needed to over-read angiograms to confirm data such as percentage of stenosis. Cooper said this may otherwise be subjective and vary by physician.

“In CORAL we are hoping we can eliminate these discrepancies,” Cooper said. “A lot of us have hope that renal stenting is a viable treatment for patients with renal stenosis. I think it is effective in some people.”

The Right Patients to Study

“We are very optimistic that the study will be concluded successfully and provide a clear answer as to the value of stenting plus medical therapy versus medical therapy alone on survival, cardiovascular and renal outcomes,” said Lance D. Dworkin, M.D., FACP, FASN, FAHA, chairman of the CORAL trial. He is also a professor of medicine, Alpert Medical School of Brown University, and physician in chief at Rhode Island and The Miriam Hospitals. He said CORAL will also show the impact of these treatments on quality of life and cost effectiveness of renal artery stenosis therapies.

He said the patient population of CORAL is much better suited for renal stenting than those in STAR or ASTRAL. “By all measures, the conduct of the trial has been outstanding,” Dworkin explained. “Most patients entered via the angiographic pathway with the average degree of stenosis above 70 percent. About 20 percent have global renal ischemia.”

Details on Renal Stenting

Renals are stented for three reasons: to treat persistent hypertension, congestive heart failure or renal ischemia (due to stenosis). The results of renal ischemia include neuroendocrine activation, hypertension and renal insufficiency. These can accelerate atherosclerosis, heart attacks and further renal dysfunction.

Hypertension patients, especially those who are unresponsive to or cannot tolerate drug therapy, are the primary candidates for renal stenting, Cooper said.

Ochsner follows the renal stenting guidelines set in 2006 by the American Heart Association (AHA) and the American College of Cardiology (ACC) which state only patients with artery stenosis of 70 percent or more should be stented. Going further, White said Ochsner uses fractional flow reserve (FFR) to measure blood flow through an occlusion to determine if it should be stented or treated medically. Patient followup is done using ultrasound to monitor the level of in-stent restenosis.

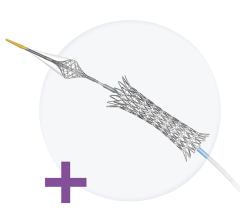

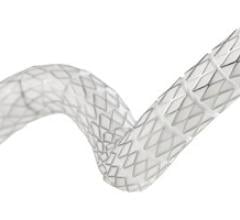

White uses the Boston Scientific Express SD, which is the only stent with a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) indication for renal stenting. He said the FDA clearance was a big help to physicians nationwide, because they no longer had to rely on off-label use of other stents.

Renal stenting has a restenosis rate of 10 to 15 percent, which is higher than coronary arteries, with rates of 8 to 10 percent, White said.

Prior to renal stenting, the standard intervention was surgical renal bypass surgery. “It is not easy to recommend a renal bypass,” White said, because of the many complications and co-morbidities involved. “You are also going to be hard-pressed to find a surgeon who will perform a renal bypass, because stenting is so effective.” He said renal bypass surgery and stenting have very similar outcomes (80 percent patency at five years). For that reason, most surgeons now opt for stenting rather than exposing patients to the much more invasive procedure.

References:

1. Bax L, Mali W.P, Buskens E, Koomans H.A, Beutler J.J, Braam B, et al. “The benefit of STent placement and blood pressure and lipid-lowering for the prevention of progression of renal dysfunction caused by Atherosclerotic ostial stenosis of the Renal artery. The STAR-study: rationale and study design.” Journal of Nephrology, 2003; 16: 807-12.

2. The ASTRAL Investigators. “ASTRAL (Angioplasty and stent for renal artery lesions): Revascularization versus medical therapy for renal-artery stenosis.” New England Journal of Medicine. 2009; 361: 1953-61.

November 24, 2025

November 24, 2025