CHRCO Volunteer Jerry Brody teaches 13-year-old Terika Brown, who just graduated high school this year and is attending college in the fall.

For some people, a new life focus is waiting just around the corner.

For Jerry Brody, it was there for 30 years — he used to drive past Children’s Hospital & Research Center Oakland (CHRCO) (Oakland, CA) on the way to work every day as a chemical engineer for Chevron. He also took his three children to the hospital for check-ups when they were growing up.

Now, with retirement and an extra degree in teaching under his belt, Brody volunteers as a bedside math teacher there.

“It’s the highlight of my week to come here and work with the kids,” he said. “I really love doing it.”

Besides having a volunteer program of over 1,000 participants at any given time, CHRCO is Northern California’s only pediatric trauma center, with expertise in 31 subspecialties.

Its cardiac center provides diagnostic, therapeutic, interventional, surgical and follow-up services for children with all types of heart disease from before birth to age 18.

The department is also participating in groundbreaking research programs in pediatric cardiology. In fact, the hospital itself is the only non-university-affiliated children’s hospital with a top 10 federally funded pediatric research center.

“It’s a great place,” Brody said while taking a break from one of his math lessons. “It’s a great hospital and a great place to volunteer.”

Detecting Iron Overload

Eric Padua, M.D., is a radiologist in the diagnostic imaging department and is part of a T2* (pronounced tee-two-star) study that is exploring ways to measure the amount of iron in muscle tissue, especially the heart.

“The only way to really get the measurement from the muscle itself right now is to do a fairly invasive biopsy,” he said. “The T2* method is a noninvasive way to quantitate that.”

T2* is a time measurement obtained from images taken on an MRI system that reflect iron content in the heart.

“There’s a certain decay curve that you can measure,” he said. “The T2* decay curve drops off a lot faster in the setting of iron than it does without iron, and the images of that muscle will actually blacken.”

That’s because a faster decay sends lower signals than a slower decay — a sign of iron overload, a common side effect for children with thalassemia.

“These patients need a lot of blood transfusions over their life span,” Dr. Padua said. “As you transfuse them with blood, you tend to overload them with iron because that’s what the red blood cells you transfuse them with contain.”

Iron doesn’t naturally excrete from the body; instead it’s deposited in the liver, muscles, bones and heart. Too much iron will eventually cause organ failure and death.

As part of their care, patients with thalassemia undergo cardiac evaluation tests in order to determine if there are any heart function abnormalities that have developed due to iron overload.

However, there is no FDA-cleared noninvasive way to specifically measure it.

“I think it was sort of unclear as to how much of a problem iron overload is for these patients until more recently,” Dr. Padua said. “So we are learning more and more as we go and as they grow into later adulthood.”

CHRCO recently began participation in the study, and Dr. Padua estimates it will be a few years before the T2* method obtains FDA approval.

Garage-to-Hospital Device

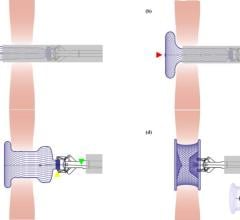

It may be surprising that a device developed in a garage and designed with fish hooks was the beginning of a noninvasive way to fix ASD, a relatively common heart defect in children, but it’s true according to Hitendra Patel, M.D.

“The early devices were very experimental,” the cardiologist at CHRCO said. “Really until the better regulatory processes were in place, that’s how people designed it.”

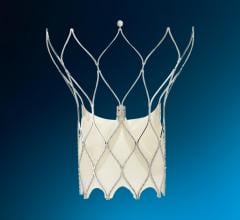

Today, the Amplatzer Septal Occluder device by AGA Medical Corp. (Golden Valley, MN) is used by the hospital to seal a hole between the two upper low-pressure chambers of the heart.

“You are trying to prevent problems early, before the children become adults,” Dr. Patel said, adding that fixing an ASD used to require highly interventional open-heart surgery.

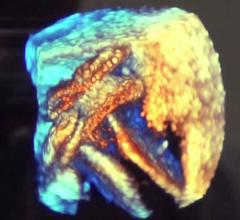

FDA cleared in 2001, the Amplatzer is a self-expandable, double disc device made from a nitinol wire mesh — a metal alloy — and is delivered via catheter.

The two discs are linked together by a short connecting waist corresponding to the size of the ASD. In order to increase its closing ability, the discs and the waist are filled with polyester fabric, which is sewn to each disc by a polyester thread.

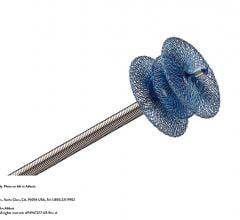

CHRCO is also part of an FDA-clearance study for a similar ASD device called the Helex Septal Occluder. However, Dr. Patel doesn’t believe this product will replace the Amplatzer device.

“It’s a similar concept, but only closes holes that are small to moderate size,” Dr. Patel said. “There is not one device that is going to be perfect for all holes.”

The Helex device is no less invasive or easier to place; however, Dr. Patel says its thinner, smaller frame conforms better to the way the heart moves because it isn’t as stiff.

June 20, 2024

June 20, 2024