August 20, 2013 — Cardiac surgeons and cardiologists at the University of Maryland Heart Center are part of a multi-center clinical trial evaluating the efficacy of powering heart pumps through a skull-based connector behind the ear. Typically, these devices for patients with severe heart failure are energized through an electrical cord connected at an abdominal site.

“Over time, nearly one-third of our patients surviving with the assistance of an implanted blood pump develop an infection at the site where the power cord exits the skin. This complication may be lethal but, if not, it is always a difficult problem,” says the University of Maryland’s principal investigator, Bartley P. Griffith, M.D., the Thomas E. and Alice Marie Hales Distinguished Professor of Surgery at the University of Maryland School of Medicine, and a senior cardiac surgeon at the University of Maryland Medical Center.

The infection-prone abdominal connection also limits some activities such as swimming and bathing, since water may also contribute to infection.

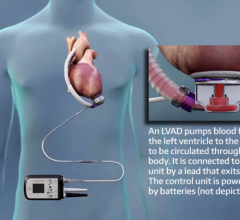

The pumps, called left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), support the heart’s main pumping chamber, the left ventricle. LVADs are implanted in the chest and powered with external batteries.

The study, named RELIVE (Randomized Evaluation of Long-term Intraventricular VAD Effectiveness), compares two similar continuous flow heart pumps designed for “destination therapy.” The devices provide long-term support to patients with end-stage heart failure who, for a variety of reasons at the time of implant, are ineligible for a heart transplant. The major difference is in the way electrical power from the battery pack gets to each pump implanted in the chest. In one case, the internal power cord is routed through a traditional opening, or pump pocket, in the abdominal wall. In the other, the internal power cable is tunneled through the neck to the head. The internal cable is connected to a socket or pedestal placed behind the ear in the skull, in the same area used to pass cochlear implant electrode wires into the body. On the outside of the skull, a waterproof cable running from the battery pack is plugged into the socket.

Patients in the study are randomly assigned to one of two groups. The treatment group receives a Jarvik 2000 LVAD equipped with an investigational “post-auricular” connector from Jarvik Heart Inc., the funder of the study. Control group patients are given a heart pump that employs an abdominal connector, Thoratec Corp.’s HeartMate II Left Ventricular Assist System, which is the most widely used FDA-approved LVAD for destination therapy.

“The bone in the skull is a better substrate to locate a foreign body on, because there’s good blood flow, and there’s no motion,” says Griffith. At the same time, the investigators posit that the location of the connector in the head should provide quality of life benefits for patients who would otherwise not be able to take a shower or swim.

The Jarvik skull model has already been approved for use in Europe. The clinical comparison in the United States opened for patients this year. The University of Maryland enrolled the second patient in the United States to receive the Jarvik pump with the skull-based connector. The study will follow 350 patients for up to three years.

For more information: www.medschool.umaryland.edu

June 19, 2024

June 19, 2024