January 7, 2016 — Scientists have found that women who suffer unexplained heart failure towards the end of pregnancy or shortly after giving birth share certain genetic changes.

The finding provides some explanation for this mysterious condition, and suggests that by testing relatives, other women who carry the same genes and who might face similar risks could be identified early. They could then be monitored closely and treated more swiftly if needed. In the future preventative treatment might be developed too.

Normal pregnancy is a challenge for the cardiovascular system, with up to a 25 percent increase in heart rate, and 50 percent increase in the volume of blood pumped in a minute. In some previously healthy women the heart just can’t cope. Around the time of childbirth the heart enlarges, and stops pumping properly – classic symptoms of heart failure. This can lead to death or the need for a heart transplant, and at the moment doctors don’t know who this will happen to.

Around 1 in every 1,000 women in Europe and the United States suffers from this condition, known as peripartum cardiomyopathy (PPCM). Elsewhere there are geographic hotspots, including Nigeria and Haiti, where the number can be as high as 1 in 100.

Women who suffer from pre-eclampsia, those pregnant with twins and older pregnant women are all known to be at higher risk of developing PPCM. The cause is unknown, though theories about contributing factors include an auto-immune response, undiagnosed heart damage, too much salt or too little selenium in the diet.

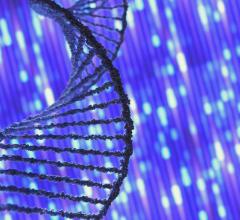

The teams found the 170 or so women they tested carried a higher number of genetic changes than normal. The team decoded genes that can cause rare inherited forms of cardiomyopathy, and found that women with PPCM had a very similar genetic profile to patients with dilated cardiomyopathy (DCM) – a condition that runs in families.

Cardiologist James Ware, clinical senior lecturer in genomic medicine at the Medical Research Council’s (MRC) Clinical Sciences Centre (CSC), based at Imperial College, is lead author of the paper describing the results, which he described as encouraging news: “DCM is managed as an inherited condition: First-degree relatives of affected individuals are offered genetic screening. Our results suggest that genetic diagnostics and family management may have similar value in PPCM.”

The study follows collaboration between researchers at a number of centers around the world including the Royal Brompton Hospital in London, Harvard Medical School and the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania in the U.S., and is published in The New England Journal of Medicine.

The researchers found that women with PPCM and patients with DCM shared abnormalities in a gene that codes for a protein called titin. Titin is the largest protein in the human body and acts like a spring within muscle tissue, including the heart. Titin’s size is crucial to its function, and some DCM is due to mutations that disrupt titin and make the protein shorter. This leads to hearts that are ‘baggy’ and stretched with thin muscle walls, that are too weak to pump blood around the body effectively, and which can cause sudden death in the 1 in 250 people affected.

The protein’s size is altered because the patients have a mutation in the titin gene. The team found this same sort of genetic change in one in ten of the women with PPCM they studied – about the same as the proportion of patients with DCM that carry this titin-shortening variant.

“Until now, we had very little insight into the cause of peripartum cardiomyopathy,” said the study’s senior author Zoltan Arany, M.D., Ph.D., an associate professor of cardiovascular medicine in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania. “There had been theories that it was linked to a viral infection, or paternal genes attacking the mother’s circulatory system, or just the stresses of pregnancy. However, this research shows that a mutation in the TTN (titin) gene is the cause of a significant number of peripartum cardiomyopathies, even in women without a family history of the disease.”

The researchers found that in women with this genetic variant their heart was pumping less well after a year. Testing for this change may therefore prove a useful way to predict likely outcome, enabling closer surveillance of those at higher risk.

Arany added: "These findings will certainly inform future peripartum cardiomyopathy research, with possible implications on genetic testing and preventative care, though more research is unquestionably needed. We’re continuing to follow these women and we’re gathering data for hundreds of others around the world, with the goal of identifying the cause of peripartum cardiomyopathy in the remaining 85 percent of women with this condition, and ultimately using what we learn to improve the care of these women and their newborns.”

This latest study was led by Zoltan Arany in the Perelman School of Medicine at the University of Pennsylvania together with professors Christine and Jon and Seidman and Dennis McNamara at the University of Pittsburgh Medical Center. Co-authors include Stuart Cook, M.D., who leads the Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance Imaging and Genetics group at the CSC; Sanjay Prasad, M.D., a consultant cardiologist and honorary senior lecturer at Imperial College; and Francesco Mazzarotto, a Ph.D. student working with Cook and Ware at the National Heart and Lung Institute.

The study builds on a substantial program of research around the role of titin in the heart by the teams from the CSC, Imperial College and Harvard.

The patients with dilated cardiomyopathy were recruited by the NIHR Cardiovascular Biomedical Research Unit at Royal Brompton and Harefield NHS Foundation Trust and Imperial College London.

For more information: www.csc.mrc.ac.uk

November 12, 2025

November 12, 2025