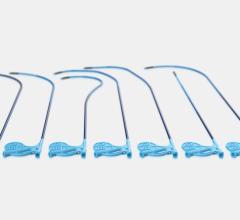

The Cook Evolution lead extraction system.

Management of implanted leads for pacemakers and defibrillators is a growing concern among physicians with more than 2 million Americans relying on a pacemaker or defibrillator to regulate their heart beat and that number growing each year. The lead is the most vulnerable part of an implantable device and the most common component to fail. As many as 20 percent of patients can expect a lead malfunction within the first 10 years after receiving the device. (1) Cook Medical estimates in the U.S. between 20,000 and 25,000 leads are extracted annually.

Removal of old leads is complicated by layers of scar tissue covering the wire in several places along its length. Removal requires torquing and cutting sheaths, both of which can perforate or tear large vessels.

Watch the 2017 VIDEO "EP Lead Extraction Strategies," an interview with Bruce Wilkoff, M.D., director of cardiac pacing and tachyarrhythmia devices at Cleveland Clinic.

Abandoning Leads

New research published in the January 2009 issue of Heart Rhythm Journal reveals that abandoning a nonfunctioning lead in an ICD patient is safe and does not pose a clinically significant risk of complication. The study suggests lead extraction should be reserved for cases of system infection or when large numbers of leads have been abandoned.

The study led by Paul Friedman, M.D., division of cardiovascular diseases at the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, MN, also a member of the Heart Rhythm Society, in collaboration with Michael Glikson, M.D., of Sheba Medical Center and Tel Aviv University, and was designed to examine the outcomes of lead abandonment and whether or not abandoning the lead posed significant risk. Patients for the study were identified by retrospective review of the Mayo Clinic ICD database with data reviewed between August 1993 and May 2002. Patient medical records were reviewed to see whether with long-term follow-up abandoned intravenous leads increased the risk of venous thromboembolic events (vein clotting), device sensing malfunction, inappropriate shocks and elevated defibrillation threshold values. The rate of appropriate and inappropriate therapies and defibrillation thresholds were compared before and after lead abandonment. Previously, there had been concern that abandoned leads might interfere with defibrillator function. Another concern was that too many leads will cause damage or regurgitation with the tricuspid valve.

“Many of the concerns about abandoning a lead in the typical patient have not panned out,” said Dr. Friedman of the study. “We found abandoning leads does not cause any harm.”

The study identified 78 ICD patients with a total of 101 abandoned leads. During a follow up of about three years, there were no signs of sensing malfunction or venous thromboembolic complications. The study demonstrated that the five-year rates of appropriate and inappropriate shocks, 25.9 percent and 20.5 percent respectively, were the same as rates seen prior to lead abandonment.

“In practical terms, for older leads, often considered those in place more than one year, leaving them in place avoids the known risks associated with extraction,” Dr. Friedman said.

He said Mayo clinic typically caps the proximal end and coils them inside the pouch in case the leads need to be removed later.

“Vascular occlusion may be an issue when abandoning four to five leads, but not with abandonment of only one or two,” Dr. Friedman said.

He admits abandonment is an area of care where there is controversy and it is not a one-size-fits-all approach. Stronger consideration to lead removal should be given in pediatric patients and younger adults when future lead replacement is expected.

“You will find people with a difference of opinion on how to handle leads,” said Brian DeVille, M.D., medical director of The Heart Hospital of Baylor Plano, TX. He tends to be more aggressive with lead removal, since the life expectancy of patients is getting longer and it is reasonable to assume patients will need new leads later in life. He said leaving multiple leads in place could also result in occluding the veins from the build up of scar tissue around the wires, or cause damage to tricuspid valve. He said the leads will build up over time if they are not removed and he has seen patients with up to six or seven abandoned leads.

“Do we pull every one out? No. If I have a 90-year-old who needs a new lead I would just abandon the old one,” Dr. DeVille said.

Releasing Scar-encased Leads

Both Drs. DeVille and Friedman use Spectranetics’ Laser Sheath (SLS II) system for lead removal. Dr. Friedman said the excimer laser system is the standard tool used at Mayo Clinic to tackle difficult leads that will not release using less invasive methods.

The Spectranetics system uses “cool” laser technology that pulse bursts of ultraviolet (UV) light energy to gently dissolve binding scar tissue into tiny particles that are easily absorbed in blood. It is a contact laser and does not use a beam that could damage surrounding tissue or perforate the vessel.

“Luke Skywalker is not going to trade in his weapon for one of these,” Dr. DeVille said.

In May 2008 Spectranetics introduced the new Lead Locking Device (LLD) EZ to aid in removing leads with its Laser Sheath. The device is fed into the hollow lead lumen and uses a braided mesh that expands to secure leads so steady traction can be applied to the lead. The tip is radiopaque, enabling verification of its location under fluoroscopy.

Dr. DeVille said the end of the lead is cut and the LLD is inserted. The laser sheath is then placed over the outer covering of the lead and uses it as a guide wire. The laser is activated when it comes in contact with scar tissue.

Dr. DeVille began using Spectranetrics laser removal system for leads in 1998. Prior to that he used the standard telescoping cutting sheaths that required physical force to rotate to cut through scar tissue. He said the laser system is much easier to use.

“It’s been very effective. Once I had access to the laser I haven’t used the telescoping sheath,” Dr. DeVille said. “It’s a lot easier on the operator and shortens the procedure time.”

He said the safety of the system is very good. In 300-350 lead extractions at his facility using this system over the past four years, he has experienced only one complication.

In a recent seven-year retrospective study, excimer laser ablation showed a success rate of more than 97 percent with only two serious complications. Laurence Epstein, M.D,, chief of cardiac arrhythmia services at Brigham and Women’s Hospital was the single operator in the study, handling 498 lead extraction procedures involving 975 leads. The study, “Large, Single-catheter, Single-operator Experience with Transvenous Lead Extraction: Outcomes and Changing Indications,” appeared in the April 2008 issue of HeartRhythm Journal. The article notes the rate of complications from abandoned leads reported in one study was as low as 5.5 percent, which Dr. Epstein said is higher than the complication rate from extraction.

A Return to Mechanical Extraction

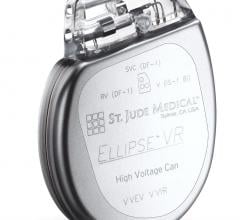

Cook Medical offers a competing technology in its PERFECTA Electrosurgical Dissection Sheath (EDS), which uses radiofrequency (RF) energy to gently dissolve fibrotic tissue, but the company said it is moving away from this device in favor of its newest device, the EVOLUTION Mechanical Dilator Sheath. Cook said its device is less invasive, more intuitive and about half the cost of laser-powered sheaths.

Charles Byrd, M.D., FACC, director of the Electrophysiology Institute at Broward General Medical Center in Ft. Lauderdale, FL, helped develop both the Spectranetics’ Laser Sheath system and PERFECTA RF system. “One was about as good as the other, but it is not a man for all seasons,” he said. “They both work pretty well, but the main problems are they don’t do well with calcium and they are slow.”

He said in 10-15 percent of his cases using laser or RF failed and he had to crossover to surgical extraction, usually through an atrial approach. Dr. Byrd also said RF energy can also stimulate nerves, sometimes causing the diaphragm to spasm.

He worked with Cook to develop EVOLUTION, which uses a squeeze- operated trigger grip handle to mechanically rotate a coring bit on the end of the sheath.

“The EVOLUTION is very fast, and it will go around calcium,” Byrd said. “Once I started using that device I haven’t had to do any crossovers. It amazes me how well it works.”

He tested the speed of the system on two11-year-old ICD leads in one patient. The EVOLUTION took eight minutes while the laser had only cut through a quarter of the way on its lead. He said the mechanical system, while being low tech, offers advantages in flexibility and overcoming the limitation of the laser optics.

Sealing SVC Tears

In 2016, Spectranetics released the Bridge Occlusion Balloon used to seal accidental tears in the superior vena cava (SVC) during EP device lead extraction procedures. A review of post-market release data shown it can bridge the patient to open surgical repair and significantly reduce the usual 50 percent mortality associated with this complication. Read the article about the late-breaking clinical trial presentation from Heart Rhythm 2017.

Read the article “ Study Shows Occlusion Balloon Saves Lives During Lead Extraction.”

Watch a VIDEO demonstrating how to use the Bridge Occlusion Balloon.

Read the article “Advances in Transvenous Lead Extraction.”

Reference:

For more information:

www.cookmedical.com

www.medtronic.com

www.CRDMPPR.medtronic.com

www.heartrhythmjournal.com

www.spectranetics.com.

February 24, 2023

February 24, 2023