September 13, 2011 – In spite of an increased attention to gender differences in treatment of myocardial infarctions, focus on adherence to guidelines and a change in predominant therapy, the gender difference in treatment and mortality regarding the big infarctions – ST-segment elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) – has not diminished from 1998-2000 to 2004-2006. For some therapies, it has actually increased.

These were the findings from Swedish RIKS-HIA registry data recently presented at the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) meeting in Paris. (This story's author, Sederholm Lawesson, M.D., from Sofia, Linkoping, Sweden presented the data.)

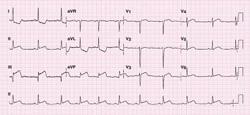

In case of STEMI, a coronary artery is completely occluded and acute opening of the artery is therefore the most important treatment. This so-called reperfusion treatment can be done in two different ways – with fibrinolytic drugs or via coronary artery catheterization with primary percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI). Historically, treatment with fibrinolytics has dominated, but since the beginning of the 21st century, primary PCI has become the preferred treatment. Studies from the fibrinolytic era found gender differences in outcome, including a higher risk of bleeding and death in women than in men, and women got less reperfusion therapy during that time. Our hypothesis was that the previously found gender difference in reperfusion therapy rate would have diminished since the shift from fibrinolytics to primary PCI.

In our study, a total of 30,077 STEMI patients were admitted during two inclusion periods, 15,697 (35 percent women) in 1998-2000 when fibrinolytics was the dominating reperfusion therapy and 14,380 (35 percent women) in 2004-2006 when primary PCI was the dominating reperfusion therapy. Among patients treated with reperfusion therapy, 9 percent were treated with primary PCI in the early period, compared to 68 percent in the late period. Mean age was the same in the two time periods.

We found that the gender gap in reperfusion treatment has not diminished between the early and the late periods – instead, it increased. In the early period, 70.9 percent of the men compared to 63.1 percent of the women, were treated with reperfusion therapy. The corresponding figures in the late period were 75.3 percent of the men and 63.6 percent of the women. After adjustment for women’s higher age and co-morbidity, they still had 20 percent less chance of getting this therapy in the late time period.

Also, all other evidence-based therapies were prescribed more rarely to women in both time episodes and the gender gap has actually increased between the periods regarding some therapies, to the disadvantage of women. Neither had the gender gap in outcome diminished between the early and the late time episodes.

In conclusion, in spite of the gender debate and focus on adherence to guidelines in the last decade, the treatment gender gap did not diminish between these two time periods – it in fact increased.

Neither did the gender difference in outcome diminish. As the RIKS-HIA register includes all patients cared for at critical care units in Sweden, we are confident that we can draw firm conclusions about gender differences in the European STEMI population in general. We have shown that adherence to guidelines needs to be increased in women with STEMI, which could probably improve their prognosis.

For more information: www.escardio.org

November 14, 2025

November 14, 2025