Abiomed's intra-aortic balloon pump

A study published in 2002, which assigned a 0-5 score to various clinical parameters, is still considered a major breakthrough in determining when to remove an intra-aortic balloon pump (IABP) and implant a ventricular assist device (VAD) in patients suffering from cardiac low-output syndrome or acute cardiogenic shock. But not everyone is convinced that a risk severity score should be the only criteria.

Should switching from an IABP to a VAD be based on a specific set of clinical parameters? Should it be at the discretion of the surgeon based on his or her own experience? Or should it be a combination of the two? “Experts in the field sit around and argue about when to implant a VAD,” said Randall Starling, M.D., vice chairman of the Department of Cardiovascular Medicine at the Cleveland Clinic and medical director of the Clinic’s Kaufman Center for Heart Failure. “But there are a lot of variables.”

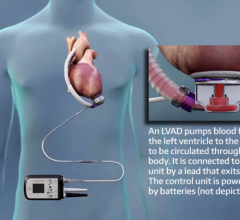

Essentially, a balloon pump is used as a stop-gap measure to stabilize a patient who has either had a heart attack or has just undergone heart surgery. “The standard therapy for a heart attack is to put a balloon pump in,” Dr. Starling said. But because an IABP can only deliver about a liter of flow, as opposed to about 2 liters or more for a VAD, a balloon pump’s function over a long period of time is limited, he added.

Margarita Camacho, M.D., surgical director of the Cardiac Transplant and Mechanical Assist Device Program at the Saint Barnabas Heart Center at Newark Beth Israel Medical Center in Newark, NJ, says balloon pumps are typically used in patients who have had acute heart failure or chronic heart failure with an acute episode such as a massive myocardial infarction.

Usually, a few days to a week with the balloon pump should be enough time to determine whether the heart has stabilized enough and there is enough blood flow to wean the patient from the pump. But she notes: “If those with an acute episode have not recovered in a week or more, you would need to start considering replacing the IABP with a VAD.”

Dr. Camacho also says it’s relatively simple to determine when to make the switch. Besides watching the patient’s hemodynamics, she uses echocardiograms during the weaning process to visualize improvements in heart function. Plus, “If the EF [ejection fraction] is better than it was before inserting the balloon, or greater than 40 percent, it’s probably safe to take it out,” she said.

For those with chronic heart failure, the only real solution is a heart transplant, Dr. Camacho says. So implanting a VAD in these patients after they’ve come off a balloon pump would serve as a bridge-to-transplant therapy.

Dr. Starling says he looks mainly at the patient’s hemodynamics. “If, with the balloon pump, urine output is poor, SVO2 [oxygen saturation] is low, high doses of medications [adrenaline], elevated pressure in the heart [LAP], low blood pressure, it is time to go for more support with a VAD.”

Piet Jansen, M.D., chief medical officer at Oakland, CA-based World Heart Corp., a leading developer of VADs, added, “If you use a pump and the patient survives, you can go to another external pump or consider implanting a VAD.” But, he warned, “If you wait too long, there’s a chance of infection or thrombosis.”

Dr. Jansen also notes that since balloon pumps are less expensive than VADs, they are often tried first.

Plus, a balloon pump can be inserted quickly, he says. “It’s used a lot because it’s easy to put in and, if it doesn’t work, it’s easy to pull it out.”

Setting Parameters

The 2002 study entitled “Prognosis After the Implantation of an Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiac Surgery Calculated With a New Score” was conducted between July 1996 and March 2000. The researchers analyzed 391 patients with cardiac low-output syndrome who had undergone open-heart surgery and had an IABP implanted.

While clinical parameters were measured, the researchers found only four as statistically significant to predict survival or death one hour after IABP implantation. These were the adrenaline requirements, urine output under maximum diuretic treatment, mixed venous saturation with a minimum hemoglobin blood level of 8 g/dL and LAP. From these four parameters, an IABP score was calculated to predict death or survival one hour after IABP implantation.

Of the 391 patients, 133 (34 percent) died within the first 30 days after the operation. In 258 patients, the IABP was explanted successfully. The mortality rate in emergency cases was 44.7 percent (68 of 152 patients) and 27.2 percent (65 of 239 patients) in the elective cases. The most common cause of death was continued ventricular failure in 85.3 percent (58 of 68 patients). Of the patients in the emergency group, three suffered from predominant arrhythmia, and seven (10.3 percent) developed septicemia followed by multi-organ failure.

By applying their IABP score, the researchers concluded, “Patients who scored five points had no probability of surviving 30 days, whereas patients with a score of zero had a probability of 86 percent.”

They further concluded: “The goal of our studies is to be able to predict the success or failure of IABP support early, providing the option, in those with low-output syndrome despite IABP support, of implanting a VAD before septicemia or multi-organ failure develops and the opportunity to ‘bridge’ such a patient to heart transplantation is lost.

“We have shown that the prognosis of patients who have an IABP implanted after cardiotomy can be calculated, while they are still in the operating room. In patients with a high IABP score and poor survival prognosis, the implantation of an assist device should be considered.”

Louis Samuels, M.D., surgical director of the heart transplantation program at Lankenau Hospital in Wynnewood, PA, did a similar study at about the same time that essentially dovetailed the Hausmann study.

Using a low-to-high-dose scale of inotropes, such as epinephrine or dopamine, combined with the patient’s hemodynamics, led Samuels and his team to conclude that higher levels of inotropes and suboptimal hemodynamics led to an increase in hospital mortality. “A patient in cardiogenic shock gets put on inotropes and the balloon pump,” he explained. “If the hemodynamics remain suboptimal, you can reliably predict what the hospital mortality will be for these patients. If it’s more than 20 to 25 percent, you should implant a VAD.”

Dr. Samuels also notes that in patients on both inotropes and a balloon pump, survival rates with a VAD are between 50 and 60 percent. Without using a VAD, mortality rates are between 40 and 100 percent.

The VAD of choice for Dr. Samuels is the AB 5000 from Abiomed Inc., but he’s also bullish on the company’s new VAD, the Impella 2.5.

In August, Abiomed announced that it had received conditional approval from the FDA to begin its pivotal clinical trial in the U.S. for the Impella 2.5 Circulatory Support System, after the company submitted clinical results of the safety pilot clinical trial.

The Impella 2.5 is a left percutaneous device inserted while in the cath lab, which provides patients with up to 2.5 liters of blood flow per minute. According to the manufacturer, it is the world’s smallest VAD and has been used to treat conditions such as acute myocardial infarction, cardiogenic shock and low-output syndrome under CE Mark approval in Europe.

Since the Impella 2.5 was designed for use on a short-term basis, Dr. Samuels said, “Some patients will go from a balloon pump to the Impella to a permanent VAD.” And while he prefers the Abiomed AB 5000, especially because it can deliver flows of up to 6 liters per minute, Dr. Samuels says he also uses the leading VADs from World Heart Corp. and Thoratec Corp. He noted, “I’m interested in the best technology for my patients.”

References:

Harald Hausmann, M.D., et al. “Prognosis After the Implantation of an Intra-Aortic Balloon Pump in Cardiac Surgery Calculated With a New Score.” 2002; 106; I-203-I-206 Circulation.

June 19, 2024

June 19, 2024