Most professional athletes participate in cardiovascular screening to identify often-asymptomatic heart disorders, but the debate continues on whether to mandate ECGs as part of pre-participation screening for student athletes. Photo courtesy of Play for Patrick.

Sudden cardiac death (SCD) is the leading medical cause of death in young athletes and its impact is consistent worldwide. Most professional athletes in the United States are required to take part in comprehensive cardiovascular screening programs to identify often-asymptomatic congenital or inherited heart disorders, and other cardiac risk factors. There remains a debate however, whether to mandate ECGs as part of pre-participation screening programs for student athletes at the collegiate and high school levels or even at younger ages.

Mandatory Screening and False Positive Results

Cardiac structure, function and electrophysiology undergo adaptive changes as an athlete increases training and fitness level. As such, ECG alterations are more prevalent and more profound in athletes who undergo more regular training. For physicians unfamiliar with these adaptive changes, however, 12-lead ECG tests can be mistakenly interpreted as abnormal and suggestive of an underlying pathological condition.

“Athletes have funny-looking ECGs,” said Victor Froelicher, M.D., FACC, FAHA, FACSM, professor of medicine at Stanford University and a cardiologist for Stanford University athletes.

Froelicher has been a key contributor to the evolution of specialized ECG criteria, and was the cardiology director at Stanford University when the school implemented an elective ECG screening program for athletes in 2007. At the time, Froelicher said he was not confident screening was in the athletes’ best interest.

“I thought when we applied this, we would find that a lot of them have unusual ECGs,” Froelicher said. “I came into this trying to protect people’s opportunities to play ball and was worried about too much of the mislabeling that had gone on to stop people from playing.”

European countries have led the way in mandating pre-participation ECG screenings. The European Society of Cardiology (ESC) currently recommends universal ECG testing for European athletes. Until their criteria were refined, however, Froelicher said that they typically saw a false positive rate of 25 percent.

“It didn’t much matter to them because they were doing (cardiac) echos and follow-up,” Froelicher said. “So it wasn’t as important as it would be in the States because we weren’t standardly doing a complete workup on every athlete.”

The problem, as Froelicher saw it, was that the criteria for ECG interpretation was based more on fairly qualified statements instead of quantified. The criteria did not specifically spell out Q waves, for instance, or how much ST segment depression was normal and in what leads.

Evolving ECG Interpretation Criteria

In 2005, abnormal ECG criteria were defined by the Study Group of Sport Cardiology of the Working Group of Cardiac Rehabilitation and Exercise Physiology and the Working Group of Myocardial and Pericardial Diseases of the ESC.

The ESC then updated its recommendations in 2010 following new research and large-population clinical investigations, creating what are considered “modern” ECG interpretation standards. Following the work of Froelicher and his colleagues in 2010 to quantify ECG abnormalities, leaders in the cardiology field met in Seattle in 2012 to update the criteria and create an online training course for ECG interpretation in athletes.

In February 2015, an international group of experts met again in Seattle to update the ECG criteria to develop an international consensus. The 2015 international criteria has been recognized by the American College of Cardiology and endorsed by the American Medical Society of Sports Medicine.

Incorporating ECG Criteria

Studies show these refined ECG interpretation criteria have been successful in reducing the false positive ECG findings rates. In one such study, the proportion of abnormal ECGs of 1,417 high school, college and professional athletes declined from 26 percent using the 2010 ESC criteria to 5.7 percent with the Seattle criteria. Another study of athletes found that using the Seattle criteria produced a false-positive rate of 2.8 percent.

Despite the success seen in using the more refined ECG criteria, only one 12-lead ECG system currently incorporates the recommended International Criteria into its automated interpretation algorithms. This system is the Cardea 20/20 ECG System, manufactured by Cardiac Insight, Inc. and was developed by Froelicher.

Froelicher said he developed the product to reduce the false-positive rate seen in typical ECG system technology. “None of the commercial machines for ECG were using the (international) criteria, and the automated programs would often call ECGs in young athletes abnormal,” Froelicher said.

The Cardea 20/20 ECG addresses another common problem clinicians face when interpreting ECG data, as often ECGs are read without the benefit of the athlete’s complete medical history. The Cardea 20/20 System integrates targeted history and physical exam questions that can accompany ECG findings to determine a patient’s risk factors and offer additional clinical context. The questions can be customized, and include whether the athlete has ever experienced chest pain or whether there is a history of cardiovascular disease in the family. Any risk factors are then noted and can be printed on the ECG.

“For instance, if there was a history of syncope, it would be there,” Froelicher said. “If the physician sees ECG that has a borderline long QT or extra betas, he/she would be more concerned knowing that the athlete has a greater pre-test probability of having cardiovascular risk.”

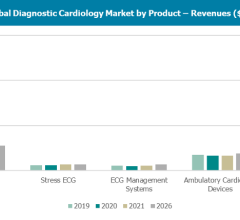

This is part of a series of articles on the newer generation of ambulatory cardiac monitors, including:

How Advances in Wearable Cardiac Monitors Improve the Patient and Clinician Experience

References

November 12, 2025

November 12, 2025