Getty Images

April 7, 2022 – The American College of Cardiology’s Global Heart Attack Treatment Initiative (GHATI) reports continuing improvements in quality care delivery for heart attacks in low- and middle-income countries with the use of data collection and localized education around guideline-directed medical therapy, according to data from the program’s second year. The findings were presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 71st Annual Scientific Session.

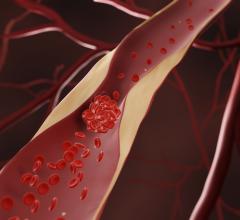

ST-elevation myocardial infarctions (STEMIs), the deadliest type of heart attack in which an artery in the heart is completely blocked, cause about 3 million deaths per year in low- and middle-income countries. While a person who suffers a heart attack in the U.S. or Europe has a 95%-97% chance of survival, the odds are significantly worse in low- and middle-income countries. ACC launched GHATI in 2019 to improve heart attack outcomes in these countries by working directly with medical centers on targeted improvements.

By the end of its second year, the program had tracked STEMI treatment metrics and outcomes for more than 4,000 patients at 39 medical centers in 18 countries on five continents. The findings revealed significant improvements in key clinical endpoints, including cardiogenic shock upon arrival at the hospital, cardiac arrest, left ventricular ejection fraction below 40% and survival at discharge, since the start of the program. Researchers also observed a continued rise in the adherence to guideline-directed medical therapy, with up to 92% of cases receiving this level of care—up from 90% after the program’s first year.

“We’re very happy to see the trends of improvement over the two-year period of data acquisition,” said Cesar Herrera, MD, Americas Representative to the ACC Assembly of International Governors, director of the CEDIMAT Cardiovascular Center in Santo Domingo, Dominican Republic, and the program’s current chair. “Measuring these data points, offering guidance to participating hospitals and encouraging them to follow guidelines seems to be working.”

While program leaders plan to design interventions in the coming years aimed at further improving care practices and health outcomes at participating sites, the first two years of the program were focused on enrolling medical centers, ensuring personnel understood ACC guidelines and facilitating baseline data collection. GHATI roughly doubled the number of sites enrolled between its first and second years, with countries in the Middle East and Latin America accounting for much of this growth. To participate in the program, which is free and voluntary, hospitals agree to collect certain data points related to STEMI care and then share the deidentified data with GHATI.

“The great thing about registries is that once you tell people what you’re measuring and why, just the fact that people are measuring and caring about those metrics can have a tremendous effect [on performance],” Herrera said. “To see the continuing improvements over time is pretty amazing.”

The two-year findings offer encouraging evidence that clinical endpoints improved for STEMI care, despite the widespread disruptions in health care caused by the COVID-19 pandemic, Herrera said. Researchers reported the primary combined endpoint dropped by an average of 3.1% between the last quarter of 2019 and the third quarter of 2021 across GHATI sites.

The results also showed a sustained high rate of reperfusion therapy—procedures to open the blocked artery—which was reported in 95% of STEMI cases. Three-quarters of patients who received percutaneous coronary intervention, the most common type of reperfusion therapy, underwent the procedure within 90 minutes of first medical contact, the critical time interval needed to save heart muscle from permanent damage and possible death. Despite an overall upward trend in this metric, this level still falls short of the recommended goal of achieving reperfusion within 90 minutes for at least 90% of STEMI patients, suggesting a possible opportunity for further improvement, Herrera said.

The data also highlighted that the time it takes for patients to get to the hospital after first medical contact can be quite long in many places. Herrera said about two-thirds of the countries represented in GHATI do not have an emergency response service like the 911 service used in the U.S. He added that in some places, practices may be constrained by technological limitations, such as a lack of echocardiographic machines for assessing left ventricular ejection fraction.

The researchers are planning additional analyses to understand the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic on care delivery and to examine how differences in a country’s income level may affect STEMI care.

In a separate study shared at ACC.22, researchers reported on gender disparities observed in STEMI care across GHATI sites. Findings from that study revealed that only about 19% of STEMI patients treated at GHATI sites were women, about half of the proportion of women treated for heart attacks at U.S. hospitals. Herrera said further research is needed to understand what may be driving this disparity, though factors such as attitudes and behaviors, access to transportation and access to care could play a role in limiting the number of women who make it to the hospital after experiencing heart attack symptoms in low- and middle-income countries.

More information about GHATI is available at ACC.org/GHATI.

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024