March 29, 2017 — In patients with a complete, persistent arterial blockage, medication alone was found to be equal to percutaneous coronary intervention (PCI) in terms of major adverse events over three years, according to a DECISION CTO trial. The trial looked at different approached to treat chronic total occlusions (CTOs). The data was presented as a late-breaking study at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2-17 Annual Scientific Session, March 17-19 in Washington, D.C. However, the trial was heavily criticized by key CTO thought leader William Lombardi, M.D., director for complex coronary artery disease therapies, University of Washington Medicine Regional Heart Center in Seattle.

Overall, about 20 percent of patients died or experienced a non-fatal heart attack, stroke or subsequent revascularization procedure (such as PCI or bypass surgery) — which together comprised the trial’s composite primary endpoint — within three years after enrolling in the study. That proportion was not significantly different for patients randomly assigned to receive PCI compared with those assigned to receive only drugs, which included aspirin, a beta-blocker, a calcium channel blocker and a statin.

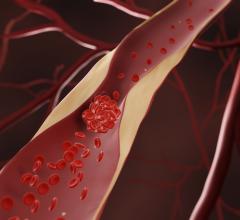

The findings are in line with evidence from previous studies suggesting that PCI does not improve long-term patient outcomes compared with medications alone in patients with coronary heart disease who have not experienced a sudden change in symptoms. This is the first study to compare clinical outcomes from the two treatment approaches in patients with a complete or near-complete blockage in the heart’s arteries that persists over time, known as chronic total occlusion. Chronic total occlusion occurs in about a quarter of people with coronary heart disease and can cause chest pain, fatigue, shortness of breath and ischemia.

“PCI is not the only solution to treat chronic total occlusion, and in terms of patient outcomes, cost versus benefit, and other considerations, it is not beneficial to use PCI for all chronic total occlusion lesions,” said Seung-Jung Park, M.D., a cardiologist at Asan Medical Center in Seoul, South Korea, and the study’s lead author. “The size of the ischemia, patient symptoms and cardiac function must be taken into account prior to the decision to perform PCI.”

The trial aimed to shed light on whether PCI or medication alone should be used as a first-line treatment for patients with chronic total occlusion. In these patients, drugs can ease symptoms and reduce the risk of events such as heart attacks and strokes, but they do not remove the blockage. With PCI, doctors thread a thin wire to the blockage via an artery and then use a tiny balloon, and sometimes also a mesh tube called a stent, to open the artery and allow blood to flow freely. Although it is frequently used in patients with coronary artery disease, PCI is more complicated when one or more arteries is fully blocked, and it has been unclear whether doctors should first use PCI or drugs alone for these patients.

The researchers enrolled 815 patients with chronic total occlusion at 19 cardiac centers in Asia. They randomly assigned 417 patients to receive PCI plus drugs and 398 patients to receive drugs alone. After tracking outcomes for three years, the results revealed no significant differences in the composite primary endpoint and no differences in rates of death, heart attack, stroke and subsequent revascularization procedures considered separately. Measures of health-related quality of life, assessed by the Seattle Angina Questionnaire, also did not differ significantly between the two groups throughout the follow-up period.

According to researchers, the findings suggest that it is not always necessary to open blocked arteries using PCI, which substantially increases costs and also can increase the risk of a heart attack around the time of the procedure.

“If patients suffer from a large ischemic burden, PCI is crucial to open the lesion, but for small occlusions, optimal medical treatment [with drugs alone] is sufficient,” Park said.

Park pointed to two potential reasons why patients with total occlusion might not benefit from opening the blockage. If a blockage builds up over a long period of time, sometimes a patient will develop new blood vessels that allow blood to circumvent the blockage, akin to a “natural bypass.” It is also possible that a total blockage actually carries a lower risk of heart attack or stroke compared with a partial blockage. Because no blood is flowing through the blockage, it may be less likely to rupture and travel through the bloodstream to the heart or brain compared with plaque that lines, but does not block, the artery.

Due to slow enrollment, the study stopped enrollment after 815 patients instead of 1,284 patients, as was originally planned. Park said interventional cardiologists may have been reluctant to enroll patients because of the predominant view that blocked arteries should be opened, despite a lack of evidence for long-term benefits of the intervention in these patients. Nonetheless, statisticians determined that the study was sufficiently large to show statistically valid results.

Criticism of the Study

Lombardi, one of the top experts in CTO interventions, said the trial was significantly flawed and lambasted the study and its data.

"In my opinion, I find it sad that an organization like ACC would allow a study that is so statistically flawed to be accepted as a late-breaking trial," Lombari said. "If that trial had shown a positive outcome for CTO, it either would not have been presented, or it every trialist on earth would slaughter it because it is not even powered properly."

He said it it was a trial testing drug A vs. drug B, it would never have even been accepted by ACC as an abstract, let alone as a late-breaking pharmaceutical trial. Lombardi said the presentation of the trial as a late-breaker was a mistake because he considers the data to be bad science. "For me, DECISION-CTO is a sign that the ACC really lost its academic credibility and it has really become a political action committee," Lombardi said.

He said the study turned away patients who were symptomatic, which to him means the researchers already believed in their therapy and were cherry picking patients. He also said the cross-over rate was about 20 percent. "If you really want a randomized trial, you need to take everybody," Lombardi said.

The lack of data on how to best treat CTOs is an ongoing issue for for cardiologists who want to the best thing for their patients, but do not have a large volume of evidence-based medicine.

"We don't have good outcome data because we have not done good studies, and we are probably not going to get them," Lombardi explained. "For a study to do this right means we need to get 1,300 patients and it's going to cost $30 million because research in the U.S. has gotten incredibly expensive."

He said a big issue with CTOs and currently available data is that decisions to treat patients are often based on pictures of the lesions. If a lesions is simple, operators tend to treat them, but if they are complex, they usually don't treat them. "What I think we should step back and do is to look if the patient has ischemia, I need to treat it no matter what the picture looks like, and if we don't have ischemia and we don't have symptoms, then we should not be treating it, even if it is a simple lesion to treat. That is a paradigm shift in our profession, we need to stop worrying about the picture and we need to step back and treat the physiology and the patient."

Park suggested that a large, global, multi-center study would allow researchers to further validate the study findings.

The trial was funded by the CardioVascular Research Foundation in South Korea.

For more information: www.acc.org

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024