April 5, 2016 — Chest pain and shortness of breath are the most common symptoms reported by both women and men with suspected heart disease, a finding in contrast to prior data. The new study was presented at the American College of Cardiology’s 65th Annual Scientific Session, April 2-4 in Chicago.

The study, which includes one of the largest cohorts of women ever enrolled in a heart disease study, also found that women had a greater number of risk factors for heart disease than men, yet these women were more likely to be characterized as lower risk not only by their healthcare providers, but also by scores that objectively measure and predict heart disease risk.

“The most important take-home message for women from this study is that their risk factors for heart disease are different from men’s, but in most cases symptoms of possible blockages in the heart’s arteries are the same as those seen in men,” said Kshipra Hemal of the Duke Clinical Research Institute in Durham, N.C., and lead author of the study.

The finding that women have more risk factors for heart disease than men means measures to reduce risk need to be a priority for women, as well as men, Hemal said.

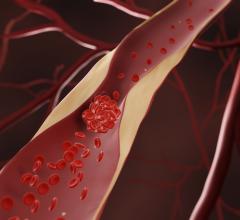

Some previous studies have suggested that women having a heart attack are less likely to have classic symptoms such as chest pain and more likely to have atypical symptoms such as back pain, abdominal pain and fatigue that may be less readily recognized as heart attack symptoms. Hemal and her colleagues sought to shed light on a different group of patients — those without a prior heart disease diagnosis who were being evaluated for symptoms suggestive of heart disease. Few studies, mostly several decades old, have examined sex differences in this group of patients.

The Prospective Multicenter Imaging Study for Evaluation of Chest Pain (PROMISE), a randomized trial conducted at 193 centers in the United States and Canada, enrolled 10,003 patients, of whom more than 5,200 were women. Half of the patients were randomly selected to receive a heart computed tomography (CT) scan, which generates 3-D images of the heart’s arteries that doctors can use to noninvasively assess the degree of narrowing. The rest received a functional or stress test — an exercise electrocardiogram, stress echocardiography or nuclear stress test — used to track the heart’s response to stress. Hemal and her colleagues examined patient data to assess differences between women and men in age, race or ethnicity, risk factors, symptoms, evaluation and test results.

The study found that, compared with men, women were older (average age 62 vs. 59 for men), more often non-white, less likely to smoke or be overweight, and more likely to have high blood pressure, high cholesterol, a history of stroke, a sedentary lifestyle, a family history of early-onset heart disease and a history of depression. Chest pain was the primary symptom for 73.2 percent of women and 72.3 percent of men. The two sexes, however, described this pain differently –– women were more likely to describe it as “crushing,” “pressure,” “squeezing” or “tightness, ” whereas men were more likely to describe it as “aching,” “dull,” “burning” or “pins and needles.” Equal proportions of women and men (15 percent) reported shortness of breath as a symptom.

Although women were more likely than men to have back pain, neck or jaw pain, or palpitations as their primary symptom, the percentage of patients of both sexes reporting these symptoms was very small (1 percent of women vs. 0.6 percent of men for back pain, 1.4 percent of women vs. 0.7 percent of men for neck or jaw pain, 2.7 percent of women vs. 2 percent of men for palpitations).

Women had lower scores than men on heart disease risk-assessment scores, suggesting a lower risk of heart disease, and before any diagnostic tests were conducted, healthcare providers were more likely to consider that women probably did not have heart disease. Nontraditional risk factors such as depression, sedentary lifestyle and family history of early-onset heart disease –– risk factors that in this study were more commonly found in women than in men –– are excluded from most risk-assessment questionnaires, however.

“For healthcare providers, this study shows the importance of taking into account the differences between women and men throughout the entire diagnostic process for suspected heart disease,” Hemal said. “Providers also need to know that, in the vast majority of cases, women and men with suspected heart disease have the same symptoms.”

Women were more likely than men to be referred for a stress echocardiography or nuclear stress test and less likely than men (9.7 percent vs. 15.1 percent) to have a positive test. Factors predicting a positive test differed for women compared with men. In women, body mass index and score on one of five risk- assessment questionnaires (the Framingham risk score) predicted a positive test, whereas in men scores on two risk-assessment questionnaires (the Framingham and modified Diamond-Forrester risk scores) predicted a positive test.

“The fact that this is one of the largest cohorts of women ever evaluated in a heart disease study lends validity to our findings,” Hemal said. A limitation of the study is that it looks only at the diagnostic process and not at whether there are differences between women and men in numbers of heart attacks or in outcomes from heart attacks, she said.

“The next step in this research will be to examine whether and how the differences we have identified between women and men influence outcomes,” she said.

The study was funded by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health. Pamela S. Douglas, M.D., led the study team.

For more information: www.acc.org

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024