May 14, 2012 – A study of more than 350 competitive athletes with implantable cardioverter defibrillators (ICDs) from around the world showed for the first time that sports may be safer for this group than has been thought. There were no occurrences of death or injury due to arrhythmia or shock during sports in this group. Additionally, only 10 percent of the athletes received a shock during competition or practice and of those, most continued to play, as reported at the Heart Rhythm Society (HRS) scientific sessions in Boston.

These results are based on a prospective study, the international ICD Sports Safety Registry. This study is the first of its kind to offer tangible evidence about the risks of sports activity in athletes with ICDs, empowering physicians to evaluate sports participation on a case-by-case basis. Currently, consensus statements recommend restriction of competitive sports for all athletes with an ICD because of the unknown risks.

“We did not know if defibrillation would work during sports…The body works differently during sports activity,” said Rachel Lampert, M.D., FHRS, lead author of the study and associate professor of medicine at Yale University School of Medicine.

“The answer to this was zero — there were no injuries,”

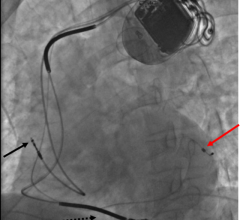

There was concern adrenaline and trauma, especially to the ICD leads, might cause the devices to malfunction. The registry followed 372 athletes from around the world for more than 2.5 years. The ages of the patients ranged from 10 to 60. About 70 percent of patients received shocks during the registry, including 30 during sports activity.

“People were getting shocked, but they were appropriate and the defibrillators worked during the sports activities,” Lampert said.

Even though people were shocked during sports, she said most athletes continued with the sport.

“These data suggest that the blanket statement that all vigorous competitive sports be restricted for patients with ICDs may not be necessary. Yet, it by no means suggests that all ICD patients should be playing sports,” said Lampert. “We believe this continues to reinforce the importance of informed and thoughtful discussions between physicians and patients, and provides new information that will help guide the final decision on whether it is safe for an individual to participate in a competitive sport with an ICD.”

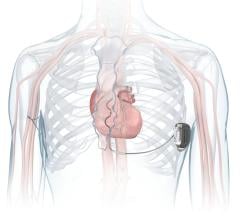

The purpose of an ICD is to convert all episodes of ventricular fibrillation (VF) or ventricular tachycardia (VT) through a defibrillation shock to the heart. Because the effectiveness of the ICD during the stressful conditions of intense sports was previously unknown, sports have not been recommended. But, the true risks have also not been known.

The study evaluated the primary endpoints of 1) death or resuscitated arrest or 2) injury during sports due to arrhythmic symptoms and/or shock. Secondary results that were monitored included system malfunction and incidence of ventricular arrhythmias (VA) requiring multiple shocks for termination. No primary endpoints occurred and of the secondary results, only ten percent of the athletes were shocked during competition or practice. Lead malfunction rates were similar to those reported previously for ICD patients leading the authors to conclude “these data do not support competitive sports restriction for all athletes with ICDs.”

The median age for participants in the study was 33, with ages ranging from 10 to 60. The most common sports were running, basketball and soccer. Athletes were recruited through physician sites and patient advocacy groups and all were already involved in competitive (n=328) or dangerous (n=44) sports.

For more information: www.HRSonline.org

January 13, 2026

January 13, 2026