Image Acquisition System by CardioOptics

It's almost like taking a stab in the dark, but ablating one or more arrythmias within the human heart is a moment when accuracy is everything and error is irreversible. Which is why visualization during cardiac ablation is one of the greatest challenges for the electrophysiologist performing the procedure.

Animal testing at the University of Chicago has demonstrated that visualization of endocardial structures and ablation lesions through flowing blood — an obstacle not previously overcome for cardiac ablation — can be achieved using infrared imaging technology. The steerable, fiberoptic, endoscopic catheter that shines infrared light through the vasculature and heart and affords unprecedented viewing through red blood cells has been developed by Boston-based CardioOptics Inc. The company's first product, the Coronary Sinus Access (CSA) System, incorporates a 7 French articulating endoscopic catheter and an infrared Image Acquisition System. It has been FDA cleared for human use in cardiac resynchronization therapy (CRT) and CRT-D pacemaker implantation procedures to facilitate placement of the left ventricular pacing lead in the coronary sinus.

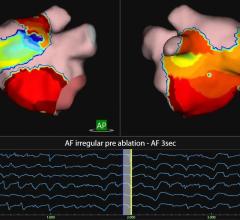

Currently, doctors perform cardiac ablation using intracardiac echo, an ultrasound-based tool, says Dr. Brad Knight, head of electrophysiology at the University of Chicago. A catheter is advanced from the femoral vein into the heart and the doctor can look at the heart from the inside. This method enables good anatomy imaging, he says, and the doctor can view the electrode-tissue interface during the ablation, seeing through many other structures.

“What we don't have is what the surgeons have,” said Dr. Knight, “which is direct visualization. They can usually directly visualize where they are cauterizing — they can see if they have created a lesion [essentially destroying and sealing off the source of the arrhythmia, or irregular heart rhythm]. One of the major limitations that still exists in electrophysiology is really knowing what is happening when you ablate.”

When doctors deliver the radio wave intended to ablate an arrhythmia, Dr. Knight says they do so without complete certainty that they've created a permanent lesion that has destroyed only its target and nothing more. Apart from the imaging modality, another way to determine accuracy is to record the signal in the heart in order to try to eliminate certain electrical signals, but this is not always sufficient evidence that a permanent ablation lesion has been created, said Dr. Knight. He also said that a temperature reading of 60-70 degrees Celsius at the electrode tip is usually indicative of a permanent lesion.

But these approaches still fall short of absolute clarity and accuracy, Dr. Knight asserts. His own recent research, however, has produced breakthrough insights.

According to a published study released in October, Dr. Knight performed 24 catheter ablation attempts in 10 mongrel dogs using infrared endoscopy. The results were that “the electrode-tissue interface could be identified at 19 of the 24 ablation sites.”

“Ablation lesion formation can be seen as a gradual increase in signal intensity,” the study's authors wrote, among whom are Dr. Knight and Ronald D. Berger, M.D., at Johns Hopkins University. “Fiberoptic infrared endoscopy appears to be a promising new tool for guiding catheter ablation,” they concluded.

The next step for the technology will be to combine the function of direct visualization and ablation into one catheter, said Dr. Knight, a process currently under development in preparation for clinical studies anticipated in 2007. At present, the fiberoptic infrared endoscope provides imaging only. Dr. Knight said that he and CardioOptics have applied for a patent for a device in which a transparent ablation electrode both enables viewing and delivers radiofrequency energy through the tip of a small diameter electrophysiology catheter.

The implications for cardiac ablation procedures in humans is significant, Dr. Knight believes.

“This might improve the understanding during the procedure,” he said, “and, theoretically, would improve the accuracy and the safety of the procedure by allowing us to really know what is going on when we ablate, to know exactly where we are ablating, and to avoid any potential complications that could occur during an ablation.”

September 05, 2025

September 05, 2025