March 29, 2020 — Worse than expected outcomes were found for survival and quality of life among patients undergoing transcatheter aortic valve replacement (TAVR) at 34 medical centers in the United States. This was according to a study of 11 percent of U.S. facilities that perform TAVR and the data they recorded with the Society of Thoracic Surgeons/American College of Cardiology Transcatheter Valve Therapy (STS/ACC TVT) Registry. The analysis was presented at the American College of Cardiology (ACC) 2020 Scientific Session.

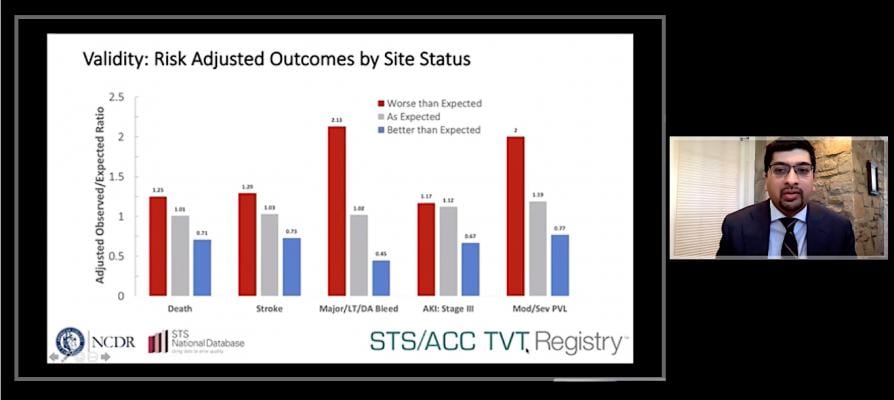

The study assessed outcomes in 54,217 patients treated at 301 sites. Eighty percent of sites had an as-expected rate of in-hospital complications, while 8 percent had better than expected complication rates. Researchers reported a substantial difference in complication rates among sites with worse than expected performance and those with better than expected performance.

“There’s clearly an opportunity to improve processes and try to better standardize care to decrease variation between different sites,” said Nimesh Desai, M.D., Ph.D., a cardiac surgeon and associate professor of surgery at the Hospital of the University of Pennsylvania, and the study’s lead author. “The overarching goal of this work is to provide transparency to the public and also to provide feedback to sites so that they can review their practices and develop ways to improve the results in their patients.”

TAVR is a procedure in which operators thread surgical equipment to the aorta through an artery in the chest or groin to replace a patient’s malfunctioning valve with an artificial one. The procedure has become increasingly popular in recent years as a less invasive alternative to open heart valve replacement surgery.

Researchers analyzed data for 2015, 2016 and 2017 from the STS/ACC TVT Registry, a Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services-mandated registry that includes nearly all patients who undergo TAVR in the U.S. From there, they created a model to assess serious complications that patients would likely want to consider when making decisions about a TAVR procedure.

“We wanted to develop a way of assessing quality using endpoints that are very important to patients,” Desai said. “Among registries for major cardiovascular procedures, this is the first metric to incorporate the patient’s functional status and quality of life, both in the risk assessment of the patient and in the derivation of the outcome measures.”

In addition to mortality, the researchers identified four key outcomes that can significantly impact patients’ quality of life a year after a TAVR procedure: stroke, life-threatening or disabling bleeding, stage three acute kidney injury and moderate or severe paravalvular leak (movement of blood across the artificial valve). The outcomes were ranked according to their impact on a patient’s daily functioning and quality of life.

Applying the metric to the registry data, researchers identified the average in-hospital complication rate across all sites and categorized sites whose outcomes were outside 95% confidence intervals of that average as performing better or worse than expected. Because it incorporates multiple outcomes on a ranked basis, the model was found to generate reliable assessments even when including sites performing a low volume of TAVR procedures per year.

The researchers plan to further analyze the data to identify any features or factors that may be associated with worse than expected performance. In addition, Desai said the model can help establish a platform for public reporting that patients and hospitals could use to inform decision-making.

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024