Image from presentation, "Affordability and Real-world Antiplatelet Treatment Effectiveness After Myocardial Infarction Study," Wang

March 20, 2018 — When patients who had a heart attack were given vouchers to cover their co-payments for medication to prevent a recurrence, physicians were more likely to prescribe a more effective, branded drug and patients were more likely to continue taking the medication for a full year as recommended in treatment guidelines, researchers reported at the American College of Cardiology’s 67th Annual Scientific Session.

“The study met its primary endpoint of improving adherence to guideline-recommended therapy at one year,” said Tracy Wang, M.D., M.H.S., M.S.c., associate professor of medicine at Duke University Medical School and lead author of the study. “When affordability was not an issue, physicians felt less restrained in their ability to choose medications, and patients were 16 percent less likely to prematurely stop taking the medication."

The study found no significant differences between patient groups for the study’s co-primary endpoint, the combined rate of heart attack, stroke or death from any cause, Wang said.

Current guidelines recommend use of antiplatelet medication — specifically, drugs such as clopidogrel or ticagrelor — for at least a year following a heart attack. Previous studies suggested, however, that adherence to this treatment regimen begins to drop off after a few months, and by one year more than one-third of patients are no longer taking their medication. Other studies have suggested that cost is a major reason that some patients stop taking prescribed medications. At least one previous study showed that treatment adherence improved when patients received their medications at no charge.

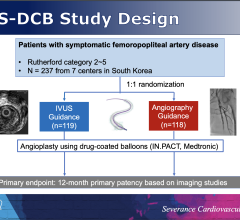

The current study, known as ARTEMIS, is the first large, prospective, multicenter trial to examine how co-payment vouchers affect patient adherence to recommended medical therapy, Wang said.

The trial enrolled 11,001 patients treated for a heart attack at one of 301 U.S. hospitals. All patients had health insurance; 64 percent had private insurance, 42 percent were on Medicare and 9 percent were on Medicaid. Seventeen percent reported previously not filling a prescription because of the medication’s cost.

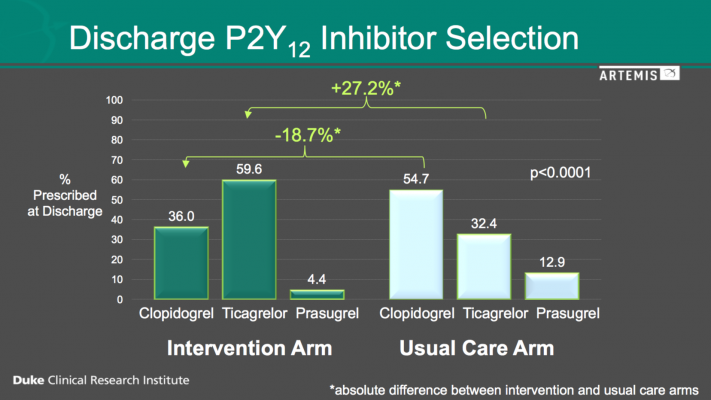

Participating hospitals were randomly assigned to either the intervention or usual-care arm of the study. At all participating hospitals, doctors used their clinical judgment to decide whether to prescribe clopidogrel or ticagrelor for each patient. At the intervention hospitals, but not at the usual-care hospitals, patients received vouchers that waived the co-pay for their prescribed antiplatelet medication for one year.

Although clopidogrel is available as a generic medication, the newer and more potent antiplatelet agent ticagrelor is currently available only as a branded product. Many patients have higher out-of-pocket costs for the same supply of a brand-name drug versus the generic version.

The study’s co-primary endpoints were continued use of the prescribed antiplatelet drug at one year without a gap in use of 30 days or more and the combined rate of heart attack, stroke or death from any cause.

Because previous studies suggested that patients may report higher rates of treatment adherence than they actually achieve, the researchers validated patient reports by analyzing pharmacy records of the prescriptions filled by 8,360 patients and by periodically testing for blood levels of the medication in a subset of 944 patients.

Among patients who received vouchers, 87 percent reported taking their medication as prescribed, compared with 84 percent of the patients who received usual care. By contrast, the analysis of pharmacy records showed an adherence rate of 55 percent for the patients receiving vouchers compared with 46 percent for those receiving usual care. In the subset of patients who had their blood tested, 92 percent in the voucher group were adherent compared with 88 percent in the usual-care group. All of these differences were statistically significant, Wang said.

“While we know that patients often overestimate their own adherence, I was surprised by the size of the discrepancy between patient reports and pharmacy fill records,” Wang said. “I suspect the ‘true’ answer is somewhere in between patient reports and pharmacy records, but both indicate that ensuring treatment adherence is still a huge problem.”

The study may have ended up with insufficient statistical power to identify a between-group difference for the co-primary endpoint, Wang said, as another surprising finding was that 28 percent of the patients who received vouchers chose not to use them. “We used vouchers to reduce co-payments because our patients were covered by multiple types of insurance and used a wide range of pharmacies and pharmacy benefit management services to obtain their medications,” she said. “But vouchers only provide the intended co-payment reduction if a patient chooses to or remembers to use it. Patients who never used the provided voucher had the highest rates of non-persistence and adverse clinical outcomes.”

Ultimately, co-payment reduction worked to improve medication prescription and use, Wang said.

“But our findings raise further questions about how best to deploy co-payment reduction to effectively improve clinical outcomes, as well as how to consider co-payment reduction strategies alongside other measures to improve patient adherence,” she said.

Wang and her colleagues said they hope to tease out answers to these questions through additional analysis of the study data.

The study was funded by AstraZeneca.

Links to all the ACC 2018 Late-Breaking Trials

For more information: www.acc.org

#ACC18

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024