April 3, 2017 — Hospitals can dramatically increase heart attack survival rates in patients suffering cardiogenic shock by providing rapid hemodynamic support before treating the cause of a heart attack, according to a new analysis that included more than 15,000 patients across the United States.

Doctors in Detroit increased survival rates from 50 percent to 84 percent by following a protocol developed using a straw-sized heart pump, said cardiologist William W. O’Neill, M.D., medical director of the Center for Structural Heart Disease at Henry Ford Hospital.

“This shows that if you can apply these best practices systematically, you can dramatically increase survival in cardiogenic shock,” said O’Neill, who presented the analysis at the American College of Cardiology’s Scientific Sessions, March 17-19 in Washington, D.C., offering to train other centers in the life-saving approach. “We believe the protocol can benefit patients nationwide.”

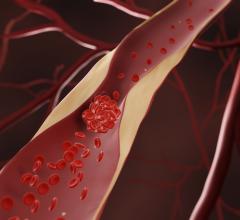

Cardiogenic shock is a complication of heart attacks that affects approximately 5-8 percent of patients in the United States annually. In these patients, the pump function of the heart is severely depressed, causing low blood pressure and vital organs to be deprived of sufficient blood supply. Despite contemporary treatments, an average of about 50 percent of patients experiencing the condition die.

The analysis looked at the use of the Impella, a straw-sized pump approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA) in 2008 and specifically for treatment of cardiogenic shock in 2016. The pump is inserted through a catheter in the groin and into the heart to keep blood pumping throughout the body. Doctors use it while they are treating the cause of a heart attack, either by inserting a stent, removing a clot or taking other necessary action while the tiny pump supports circulation.

Watch the VIDEO "Demonstration of the Impella Percutaneous Hemodynamic Support Device."

The analysis retroactively looked at data collected by Abiomed, the pump’s manufacturer, in 15,529 patients – 72 percent men and an average age of 63 – treated between 2009 and 2017.

The investigators noticed that survival rates in patients treated with the Impella pump fluctuated wildly by hospital, O’Neill said. A third of hospitals experienced a 25 percent survival rate; a third, 50 percent survival; and a third, 75 percent.

“There was a huge variation in outcomes between the centers, between the lowest performing and highest performing centers,” said O’Neill. “It looked as though putting the Impella in soon, before you do anything else, is connected to survival.”

Inserting the pump first ensures the patient’s other vital organs are supported, buying time for cardiologists to open the blocked arteries to restore natural blood flow. The hospitals with high survival rates also used less inotropes and correctly sized catheters to monitor heart pressure, O’Neill added.

To test the best practices, O’Neill organized five hospital systems in southeast Michigan to follow a specific protocol in ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI) patients who showed signs of cardiogenic shock between July 2016 and Jan. 2017. Of the 37 patients supported with the Detroit Cardiogenic Shock Initiative protocol, 31 (84 percent) survived.

“Some of these breakthroughs are so straightforward, you wonder, why didn’t we think of it before?” said O’Neill. “We believe this approach can benefit patients nationwide.”

Participants with Henry Ford Health System in the Detroit Cardiogenic Shock Initiative include Beaumont Hospital, Detroit Medical Center, Ascension’s St. John and Providence hospitals and Saint Joseph Mercy Health System.

“Cardiologists have been trying to move the needle on heart attack survival rate for years; this is a huge success,” said Thomas Lalonde, M.D., chief of cardiology at St. John Hospital in Detroit.

Key to the protocol is medical personnel recognizing cardiogenic shock in patients as soon as possible, O’Neill added.

“If they think the patient needs medication to raise the blood pressure, that’s when they should be thinking, ‘Get them someplace where they can get a pump implanted,’” said O’Neill, who intends to help other hospital systems across the United States implement the protocols.

For more information: www.henryford.com/cardiogenicshock

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024