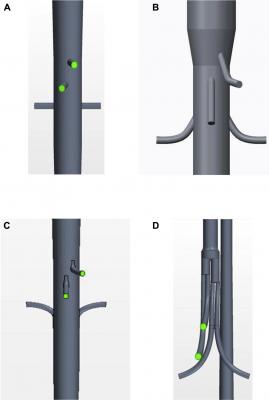

An anterior view is shown of the geometries of each of the graft configurations: (A) fenestrated, (B) antegrade branched, (C) retrograde branched, and (D) manifold stent graft. Image courtesy of Taylor Suess, et al.

January 5, 2017 — Whether patients with mechanical heart valves and stents must take blood thinners depends on how effectively blood flows through these implantable medical devices. Researchers have modeled the flow of blood through left ventricular assist devices and mechanical heart valves to estimate clotting risk, but this type of work has not been done on stent grafts — until now.

South Dakota State University associate professor Stephen Gent collaborated with Sanford Health vascular surgeon Pat Kelly, M.D., and biomedical engineer Tyler Remund to evaluate whether a new branching stent design might increase the risk of blood clots. Their work was accepted for publication in the Journal of Vascular Surgery and is available online.

“An orderly straight-through flow is optimal,” explained Gent, who has done computational fluid dynamic modeling of stent grafts for the Sanford team since 2014. This work builds on a previous model that provided supporting evidence for well-developed blood flow through a similarly-designed stent, which is now part of a U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA)-approved investigational device exemption, or IDE, clinical trial. Those results were published in the September 2016 Journal of Vascular Surgery.

Only a small number of patients — two per 100,000 a year — are diagnosed with thoracoabdominal aneurysms, according to Kelly. However, most of those patients would not survive traditional open surgery, which involves an incision from the shoulder blades to the groin. The flexible, branching stent grafts that Kelly designs may provide a less invasive alternative.

Of particular concern, was the flow through a section of the branching stent graft where the blood from the main channel or aorta branches to the celiac artery, superior mesenteric artery and renal arteries that transport blood to vital organs, according to Remund. “The FDA wants to make sure that you’ve assessed the risk-benefit ratio and addressed as many risks as possible.”

The researchers incorporated aspects of a flow model designed to assess the likelihood of clots forming in mechanical heart valves into their stent graft model. Then they compared the results with those from two mechanical heart valves and an idealized aorta.

“As we expected, Kelly’s design performs an order of magnitude lower than was reported for the mechanical heart valves, both of which are FDA-approved for IDE clinical trials,” said Gent, who is the first mechanical engineering department faculty member to do this type of research. Furthermore, the blood flow through the stent graft was comparable to that of the idealized aorta.

“Vascular surgeons want the flow to be laminar, so it does not induce turbulence,” Gent explained. When the blood flows becomes more disturbed, this induces more shear stress on the platelets in the blood. This shear stress over time, also known as shear accumulation, can damage or activate platelets, what causes them to form clots. These clots can break off and go downstream where they can easily block blood flow to vital organs, such as the stomach and liver. This is known as thromboembolism formation.

“We are tracking representative blood particles to determine the likelihood of platelets becoming activated,” Gent pointed out.

Using the model, he assessed shear accumulation for three stent graft diaphragm angles — 0, 20 and 40 degrees. Results showed that the moderate 20-degree angle created the most efficient flow pattern, with shear accumulation in the 1.0 to 1.5 Pascal-seconds range for 99.9 percentile of particles.

The industry is trying to come up with standardized methodologies and a consensus among experts about what an acceptable set of boundary conditions should be for blood flow through branched stent grafts, according to Remund.

“While developing this model, we were able to study how others approached devices, such as left ventricular assist devices [LVADs], that are known to activate platelets,” he explained. LVADs are pumps that can support the blood circulation in patients with severely weakened hearts and consequently tend to create a lot of shear effects on the blood.

“As we continue to push the envelope as an industry, we want to make sure we are not creating unforseen problems for patients,” Remund pointed out.

Though this project focused on shear accumulation, Gent said, “We are expanding our portfolio of capabilities to evaluate these stents for various types of relevant parameters. We are trying to answer really tough questions while also being responsible as we work through it.”

For more information: www.jvascsurg.org

September 18, 2025

September 18, 2025