April 8, 2024 — People with diabetes who had suffered a heart attack derived no clinical benefit from edetate disodium-based chelation, a therapy that draws lead and other toxic metals linked to increased risk of heart disease and stroke out of the body, according to a study presented at the American College of Cardiology’s Annual Scientific Session.

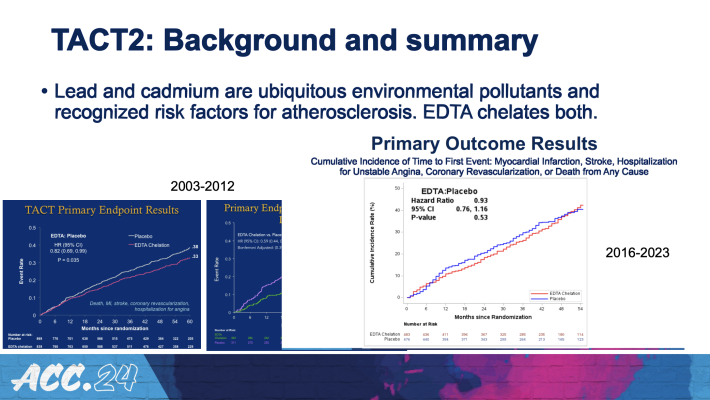

The TACT2 study was designed to replicate the results of a previous trial, TACT, which reported in 2012 that chelation reduced subsequent cardiovascular events after a heart attack. However, the TACT2 results did not reveal any difference in the composite primary outcome of death from any cause, heart attack, stroke, coronary revascularization or hospitalization for unstable angina among people who received weekly edetate disodium-based infusions compared with those who received a placebo.

Gervasio A. Lamas, MD

“Despite effectively reducing lead levels, edetate disodium-based chelation was not effective at reducing cardiovascular events in U.S. and Canadian patients with diabetes and a history of heart attack,” said Gervasio A. Lamas, MD, chair of medicine and chief of the Columbia University Division of Cardiology at Mount Sinai Medical Center in Miami and the study’s lead author. “At the present time, in a contemporary population with low lead levels, edetate disodium-based chelation is not effective as a therapy for post-heart attack patients.”

Chronic exposure to lead and cadmium can cause damage to cells and blood vessels by blocking the action of essential elements such as calcium and zinc in vital biochemical processes. Chelation involves intravenous infusions of edetate disodium, a chelating agent that binds to metals such as lead and cadmium and is excreted in the urine. Edetate calcium disodium, a slightly different compound, is approved by the U.S. Food and Drug Administration to treat lead poisoning, but studies investigating its use for other conditions have yielded mixed results.

The original TACT trial, which ran from 2003 to 2012, suggested modest benefits from edetate disodiumbased infusions in reducing cardiovascular events after a heart attack over a median follow-up of 55 months, especially in people with diabetes.

TACT2, which began enrollment in 2016, involved 1,000 patients with mostly Type 2 diabetes (over 90% of enrolled patients) and a previous heart attack at 88 sites in the U.S. and Canada. Patients were randomized to receive either active treatments, which consisted of 40 weekly edetate disodium infusions or a corresponding placebo. Overall, 68% of participants received all 40 of their assigned infusions and 78% received at least 20 infusions.

After a median follow-up of 48 months, no significant difference was observed in the rates of the primary composite endpoint, which occurred in about 35% of patients in both groups. However, over this same period the level of lead in participants’ blood dropped by an average of 61% among those who received chelation compared with those who received a placebo. The chelation therapy also showed a good safety profile, with no increased risk of serious adverse events and no unexpected serious adverse events reported in the chelation group.

Researchers said that two factors may help explain why TACT and TACT2—which were overseen by the same study team and involved the same medications and study protocols—ultimately had different results. One is that participants in TACT2 may have had more advanced diabetes and more severe associated health impacts than those in the first TACT trial, reducing the trial’s ability to meaningfully impact clinical outcomes. The second is that participants’ baseline lead levels were more than 30% lower in TACT2 than in TACT. This likely reflects the fact that public health interventions, such as the elimination of leaded gasoline, have successfully reduced lead exposure in most developed countries over the past several decades.

Although either or both of these factors could have blunted the ability for chelation to reduce cardiovascular events in the new study, Lamas said that the study’s findings in terms of overall lead reduction could still be relevant for informing health interventions in the majority of the world where lead exposure is more common.

“Our method of treatment was effective at reducing lead, even in patients starting with low lead levels, and it was safe,” Lamas said. “In most countries outside of North America and western Europe, lead remains a serious cardiovascular and neurological problem. This study may be more relevant to those areas of the world, but this is a hypothesis that requires further study. For now, however, edetate disodium-based chelation does not have a role in treating U.S. and Canadian patients with diabetes and a prior heart attack,” Lamas said.

The study was funded by the National Institutes of Health.

For more information: www.acc.org

Find more ACC24 conference coverage here

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024