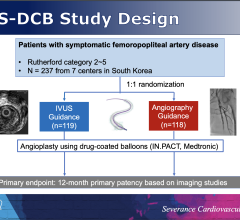

An intravascular ultrasound (IVUS) image of a thrombus formed in a coronary artery. While there are guidelines for antiplatelet therapy, there are still questions over the duration of such therapy.

There were many opinions on the duration of dual antiplatelet therapy (DAPT) highlighted at the 2016 American College of Cardiology (ACC.16) meeting. A general theme was DAPT prolongation and patient stratification, which was relevant to the recent release of the ACC and the American Heart Association’s (AHA) 2016 Focused Update in Duration of DAPT in Patients with Coronary Artery Disease (CAD). Although sessions at ACC.16 helped clarify the recent guidelines, questions still remain.

Drugs Used for DAPT and Potency

This guideline-focused update is supported by the inherent characteristics of the drugs. Thienopyridines (clopidogrel [Plavix] and prasugrel [Effient]) irreversibly inhibit platelet activation by inhibiting the P2Y12 receptor and blocking adenosine diphosphate (ADP) binding to the receptor. This prevents platelet and thrombus aggregation. Ticagrelor (Brillinta) has a similar net effect, but it reversibly binds to the P2Y12 receptor, bypassing the ADP binding site. The newer P2Y12 inhibitors prasugrel and ticagrelor have a quicker onset of action and potency than clopidogrel. Clopidogrel’s rate-limiting factors are that 85 percent of the pro-drug is deactivated prior to intestinal absorption, and the remaining pro-drug requires metabolic activation via hepatic cytochrome P450 pathways. Also, patients with CYP gene variations may express polymorphisms in the CYP2C19 allele, which is integral to clopidogrel’s conversion to an active drug. The combination of these factors lead to intra-patient variability and a prolonged time to therapeutic effects.[1]

The ACC/AHA’s 2016 Focused Update in Duration of DAPT in Patients with CAD has evolved to complement the 2014 European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) guidelines on myocardial revascularization.[2,3] The guidelines agree on the recommendation for low-dose aspirin with ticagrelor or prasugrel over clopidogrel for maintenance therapy after acute coronary syndrome (ACS), non-ST elevation-ACS (NSTE-ACS) or ST-elevation myocardial infarction (STEMI), post-coronary stent implantation and in patients with NSTE-ACS treated with medical therapy alone.[3] The ESC/EACTS guidelines slightly differ from the ACC/AHA guidelines when recommending prasugrel. Prasugrel is currently contraindicated in patients ≥75 years of age, low body weight (< 60 kg), prior history of stroke or transient ischemic attack (TIA).[1]

The AHA/ACC guidelines recommend prasugrel over clopidogrel if the patient does not have a high risk for bleeding complications, history of stroke or TIA. The ESC/EACTS guidelines suggest allowing treatment with prasugrel in patients ≥75 years of age or <60 kg if the patient has been evaluated for risk versus benefits. In this case, a reduced maintenance dose of 5 mg may be prescribed.[2] The guidelines are similar with regards to DAPT duration recommendations (Table 1). The ACC/AHA guidelines do recommend a reduction in P2Y12 inhibitor therapy duration to three months for stable ischemic heart disease or six months for acute coronary syndrome in patients that after DAPT have developed a high risk for bleeding, severe bleeding complication or overt bleeding. This reinforces the findings that the optimal duration for prolonged DAPT has not been established.

Although the focused update helped clarify drug recommendations and duration for DAPT in CAD patients, there are relevant points that were highlighted by this year’s presenters at ACC.16. Several studies were mentioned with specific supporting points. In a meta-analysis by Elmariah et al., it was found that prolonged DAPT versus short-term DAPT versus aspirin alone did not increase the risk of cardiovascular or non-cardiovascular death.[4] In a study by Mauri et al., and a meta-analysis by Guistino (2015), they countered the above results by finding that prolonged DAPT beyond 12 months post-coronary stenting was associated with an increased risk of non-cardiovascular death and all-cause mortality, respectively.[5,6] The main argument became how to balance the potential benefit of prolonged DAPT to the detriment of mortality or bleeding. Based on these findings, it was suggested by Toulio Palmerini, M.D., research scholar at Cardiovascular Research Foundation, and a cardiologist at S.Orsola Malpighi Hospital in Bologna, Italy, that DAPT duration may be patient-specific.

Ischemic/Stent Thrombosis Risk vs. Bleed Risk

The presenters concluded that individualized therapy should be based on risk of ischemia or stent thrombosis versus risk of bleeding, and the ACC/AHA focused update defined the criteria (Table 2).[3]

According to the PARIS Registry, most PCI patients (about 70 percent) are low bleed risk, argued Robert Yeh, M.D., MSc, MBA, director of the Richard A. and Susan F. Smith Center for Outcomes Research in Cardiology at Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston.[7] It can be inferred that if most patients have a low bleed risk then they might benefit from prolonged DAPT.

To the contrary, ACC.16 speakers Yeh, Palmerini and Laura Mauri, M.D., MSc, director of the Division of Cardiovascular Medicine’s Center for Clinical Biometrics and Harvard Clinical Research Institute at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, agreed that individualized therapy was important and that the use of the DAPT score was an option. They mentioned that the lower the DAPT score, the lower the benefit of prolonged DAPT when compared to the risk of bleeding. On the contrary, the higher the score the higher the benefit when compared to the risk of bleeding. Mauri emphasized that prolonged duration is independent of stent type and stressed treating the patient.

DAPT Score Explanation

The DAPT Trial prolonged DAPT from 12 to 30 months in patients that received either a drug-eluting stent or a bare metal stent.[5] At a high score, the investigators observed a reduction in ischemia and a small increase in bleeding. At a low score, there was an increase in bleeding and a smaller reduction in ischemia. Per the ACC/AHA guidelines, a score ≥2 is linked to a favorable benefit to risk ratio in prolonging DAPT, and a DAPT score <2 has an unfavorable ratio.[3] The DAPT score takes several factors into account (Table 3), but age ≥75 years old was associated with worse outcomes.[3,5] Based on the above, patients with scores ≥2 may benefit from an additional 18 months of therapy. Although DAPT score approximates a solution to stratifying patients to prolonged DAPT, it has not been validated outside of the DAPT trial, which did not evaluate patients using ticagrelor or anticoagulants.[5] Patients who are clinically at risk for bleeding or have a minimal perceived advantage may not benefit from DAPT score stratification.

Prolonging DAPT and Balancing Bleeding Risks

If a provider chooses to prolong therapy, it should be recommended along with careful review. Patients should be evaluated for bleed risk at certain intervals. Patients should be assessed once initiated on DAPT after one month and if they have a history of prior bleeds, suggested Gilles Montalescot, M.D., Ph.D., professor of cardiology and head of the department of cardiology at the Pitié-Salpêtrière Hospital in Paris. At six months, patients should be evaluated based on gender (females are at greater risk of bleeding), history of low hemoglobin and low/high body weight. At 12 months, patients with no risk factors or those with low bleed risk and high ischemic risk may be continued on therapy. This mimics the recommendations brought forth in the ACC/AHA focused update.

The Unknown Factors of DAPT

Although recommendations can be pieced together after reviewing current guidelines, DAPT score and clinical conundrums, some questions have still been unanswered. Further studies are needed to investigate the incidence of thrombotic effects when discontinuing thienopyridines after minimum recommendations, said Sanjay Kaul, M.D., director, cardiology fellowship program at Cedars-Sinai Medical Center, Los Angeles. Michael Gibson, M.D., interventional cardiologist, cardiovascular researcher and educator, Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center, Boston, alluded to about 10 ongoing trials evaluating the discontinuation of aspirin from DAPT or from triple therapy, including anticoagulants. Pending the results from these clinical studies, clinicians are still encouraged to use their clinical judgment when prolonging DAPT, speakers said.

Read the February 2017 article “Rivaroxaban Shows Superiority Over Aspirin in Patients With Coronary and Peripheral Artery Disease.”

Read the article “Advantages and Disadvantages of Novel Oral Anticoagulants.”

Editor’s note: Marianne Pop, Pharm.D., BCPS, is a clinical pharmacist and clinical assistant professor with the regional pharmacy program, University of Illinois at Chicago College of Pharmacy. She specializes in emergency medicine pharmacy as part of the regional pharmacy program at OSF Saint Anthony Medical Center in Rockford, Ill.

References:

1. Damman P, Woudstra P, Kuijt WJ, de Winter RJ, James SK. “P2Y12 platelet inhibition in clinical practice.” J Thromb Thrombolysis (2012) 33:143–153.

2. Authors/Task Force members, Windecker S, Kolh P, et al. “2014 ESC/EACTS Guidelines on myocardial revascularization: The Task Force on Myocardial Revascularization of the European Society of Cardiology (ESC) and the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS) Developed with the special contribution of the European Association of Percutaneous Cardiovascular Interventions (EAPCI).” Eur Heart J 2014; 35:2541.

3. Levine GN, Bates ER, Bittl JA, et al. “2016 ACC/AHA Guideline Focused Update on Duration of Dual Antiplatelet Therapy in Patients With Coronary Artery Disease: A Report of the American College of Cardiology/American Heart Association Task Force on Clinical Practice Guidelines.” J Am Coll Cardiol 2016.

4. Elmariah, S, Mauri, L, Doros, G et al. “Extended duration dual antiplatelet therapy and mortality: a systematic review and meta-analysis.” Lancet. 2015; 385: 792–798.

5. Mauri, L, Kereiakes, DJ, Yeh, RW et al. “Twelve or 30 months of dual antiplatelet therapy after drug-eluting stents.” N Engl J Med. 2014; 371: 2155–2166.

6. Giustino, G, Baber, U, Sartori, S et al. “Duration of dual antiplatelet therapy following drug-eluting stent implantation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials.” J Am Coll Cardiol. 2015; 114: 236–242.

7. Mehran R, Baber U, Steg PG, et al. “Cessation of dual antiplatelet treatment and cardiac events after percutaneous coronary intervention (PARIS): 2 year results from a prospective observational study.” Lancet. 2013;382:1714-22.

July 31, 2024

July 31, 2024